The AI world models debate and its foreshadowing on robotics

Plus, five facets of comparison for the two approaches

Large language model (LLM)-based tools such as chatbots, coding assistants, and writing aids have become widely adopted and have had significant cultural and economic impact and utility. At the same time, the conversation continues about what kinds of progress these models represent and what their limitations may be. One of the central questions in this discussion is whether “scaling” improvements in LLMs (primarily achieved through larger models and larger training datasets) can lead to general intelligence, or whether additional architectural or conceptual advances will be required.

In parallel with these debates, especially on the heels of numerous announcements at CES 2026, the cultural focus is increasingly driving toward robotics or “physical AI”; is there a physical equivalent to this intellectual debate between scaling and structured models?

Here, we’ll try to go over some of the key aspects of this intellectual and conceptual spectrum starting with the informational world, and examine the implications of the equivalent schools of thought in the physical world.

This publication and this post contain the author’s personal thoughts and opinions only, and do not reflect the views of any companies or institutions.

Today’s AI is a product of scaling a simple architecture (mostly)

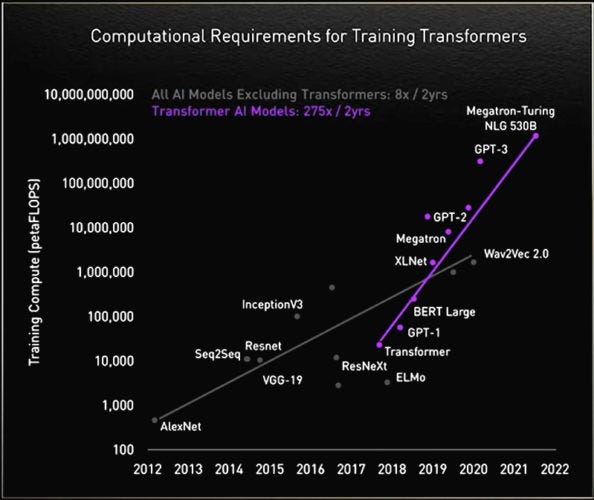

Breaking down this heading, by “today’s AI,” I’m referring to the most pervasive products, such as chatbots, search, coding and writing assistants. These systems are typically based on large transformer architectures composed of many repeated layers and trained on vast datasets, with models today having hunders of billions of parameters.1 In simplified form, these systems operate by mapping input tokens into embeddings, processing them through a stack of transformer blocks, and producing probability distributions over possible next tokens via a final linear projection and softmax layer.

Since the initial release of ChatGPT, the dominant trend in the development of these models has been to increase their size and the amount of data used for training, rather than to introduce fundamentally new architectural principles.

Given this architectural simplicity, the range of capability expressed by LLM-based tools is frankly impressive. Much of this capability therefore arises from the interaction between large model size and extensive training data, rather than from task-specific design and bespoke computational structures.

Sam Altman’s early 2025 blog post and the empirical observations of companies building LLMs added on evidence and expectation of continued scaling of intelligence this way. These observations led to a “scale is all you need” movement that has had enormous impact on our society and economy, with $1.7 trillion of projected investment by 2030.

The larger debate we’re looking at in this post is about the prediction that scale is sufficient (more below), but it is also important to ask if it is necessary. I.e. is scale required to exhibit the same progress? The answer to this is likely yes; as stated in a Dec 2025 preprint by Quattrociocchi et al, when the models are restricted to the transformer architecture described above, it appears to be true that “their apparent intelligence emerges only under conditions of massive scale”.

Another natural question is why there has been so much investment into exploiting scaling, vs. exploration of other architectures. The first is that progress is consistent and predictable (even suggesting scaling “laws” as in the Altman blog post) which enable predictable engineering and financial projections. Innovation and development of new architectures is a relatively unpredictable and risky process. Another very prominent virtue is that simple architectures are much easier for collaboration with other parts of the engineering stack, and has been key for the adoption of hardware acceleration for deep learning.

Many leading researchers such as Demis Hassabis, Geoffrey Hinton, and teams at OpenAI and Anthropic maintain that scaling remains a primary driver of progress.

The other side of the AI debate

Over the recent past, there have been an increasing number of arguments disagreeing with the claim that scaling is sufficient to get to arbitrary “intelligence.”

Per the March 2025 findings of the annual meeting of the AAAI, including responses from more than 475 members (67% of them academics),

More than three-quarters of respondents said that enlarging current AI systems ― an approach that has been hugely successful in enhancing their performance over the past few years ― is unlikely to lead to what is known as artificial general intelligence (AGI).

Well-respected AI researchers are starting to form the next wave of AI companies that try to encode some kind of “world model” or semantic understanding of the world: Dr. Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs generates images and videos but only via an intermediating representation of a 3D world. Yann LeCun’s new startup AMI labs is likely also building world models via some form of his published JEPA work. Ilya Sutskever (one of OpenAI’s founders, who had a large contribution to Sam Altman’s perspective above) went on Dwarkesh’s podcast and said that scaling alone would not carry us to AGI and that “something crucial is missing.” Cognitive scientist Gary Marcus has frequently writes about the need for symbolic reasoning for AI and is often in the thick of the debate on how to get there.

What is a world model?

There is at present no clearly-victorious architecture for how to encode added structure in large AI models. Consider a few examples from the AI world:

World Labs, whose product generates consistent images and video, would define it as metric information about a 3D scene

Many AI researchers using a working definition for a world model as a (potentially latent-space) dynamical model that predicts how the state of the world evolves under actions.

Schmidhuber wrote a paper about world models in 1991, with the working definition as “predicting future sensory data given our current motor actions”

Yann LeCun proposes learning and predicting latent-space dynamics in his JEPA research (papers 2022-2025) — crucially, the projection to latent space is also learned from data, making it more general but less grounded in physical laws

The 1x world model is described in Jan 2026 as having latent space prediction capability and used to generated predicted future video states

DeepMind’s 2025 paper also seeks a ”predictive model of its environment” — In the paper it is a markov process, but for a continuous system such as a robot, it would be continuous or discretized dynamics governed by physics. It does not, however, specify how one would design architectures to take advantage of world models: “Future work should explore developing scalable algorithms for eliciting these world models and using them to improve agent safety.”

Zooming out to broader science, models have been developed and used in almost all fields; biologists have been discovering models for navigation in animal brains, physicists have been developing models for the behavior of the universe from quantum to astronomical scales for centuries, civil engineers have been using models of mechanics to build our houses and bridges, etc. Gary Marcus defines a cognitive world model as “a computational framework that a system (a machine, or a person or other animal) uses to track what is happening in the world … persistent, stable, updatable (and ideally up-to-date) internal representations of some set of entities within some slice of the world.” Each of these parties would likely have different opinions on models of the world / universe that AI should be imbued with.

In this post, we’ll stay focused on whether the added structure is important, but not discuss the relative merits of these varied proposals. (That is a potential topic for future posts; make sure to subscribe to get notified when they get published)

Why do we need world models?

The critical view is that while LLMs are designed to predict what to do next, but are not designed to build an underlying semantic understanding, and that there are many examples of errors (or “hallucinations”) that can ultimately be root-caused to this:

LLMs can parrot rules of chess but will make illegal moves at the same time, they do not generalize well to out-of-training scenarios or under uncertainty and can produce unpredictable responses to uncommon inputs such as SolidGoldMagikarp, they exhibit “semantic leakage” of concepts and semantics in their input streams, with real-world impacts on usage of AI for policing. While capabilities of LLMs do keep increasing, there is concern that errors such as these cannot be universally eradicated without an architectural shift.

Is there an equivalent debate in robotics?

Humanoid robotics in particular has been having a prominent rise into the cultural and economic consciousness in the last few years. Humanoids have been featured at NVIDIA keynotes for about two years now, clearly signaling that the time is here for robotics companies to show their products and get mass-market adoption. While the field of robotics has existed for a long time, it is undeniable that the capabilities demonstrated have been seeing large improvements along with this increased exposure to the public eye.

Does the same architectural divide we just discussed for LLMs also exist in robotics? Less is known (much less agreed upon) about the best way to develop advanced capabilities in these robots, but we can use public information from some companies that have made product announcements to guess some patterns:

The Boston Dynamics CEO says that they “need to be able to bring a new task to bear in a day or two … because, I think in a factory, there’s literally hundreds of tasks and the tasks evolve,” and their 60 minutes feature shows the ability to rapidly deploy motion capture or VR demonstration data to their Atlas robot

Figure describes its “Project Go-Big” as an effort to collect human demonstration data in the form of first-person video for pre-training2 a navigation model

1x described its plan to collect teleoperated demonstration data with its robot in people’s homes for continued training of its AI model in Oct 2025, and released an update in Jan 2026 suggesting learning from internet-scale videos as demonstration followed by RL in simulation

I want to note that all these companies have very intelligent researchers and engineers on their staff, and it is very possible (and likely) that there is more going on in these particular demos; I only include these specific reference points as context to pick out broad themes. Some surfacing patterns are that (a) the rate at which different tasks are demonstrated is a high priority for these companies, (b) many of them are looking to pre-training with motion data collected from humans, and (c) this will be followed by post-training using reinforcement learning (most likely in simulation) where the system’s reward will include matching the demonstration.

My rough summary here is largely echoed by Rodney Brooks in his 2025 post on humanoid robot dexterity:

How the humanoid companies and academic researchers have chosen to do this is largely through having a learning system watch movies of people doing manipulation tasks, and try to learn what the motions are for a robot to do the same tasks. In a few cases humans teleoperate a robot, that they can see, along with the objects being manipulated ...

A robotics parallel of LLM development

Very roughly, the training process for both status-quo approaches have similar-looking steps:

pre-training - reading internet-scale text (LLMs), vs. watching internet-scale human demonstration video or motion data (robots);

post-training - RLHF and its modern equivalents vs. RL in simulation followed by sim-to-real porting and deployment

With this grounding, we can ask whether robotics applications will run into the same problems and debates as we discussed for LLMs above.

One unknown is whether motion data is the best analogue of text data. Rodney Brooks articulates some concerns about this in his dexterous manipulation essay, suggesting that tactile sensing data is needed (but internet-scale tactile sensing data, or any other kind of robot data, doesn’t exist). It is likely that all the robots will include tactile sensors in some form, but it isn’t clear yet how they will fit into this human demonstration large-data paradigm.

The larger question is whether a navigation capability trained with motion data will generalize to unseen and unexpected situations, since it is not designed to encode an explicit understanding of “objects” or “inertias” or “positions”. This concern exactly mirrors the ones about semantic understanding in LLMs. It is likely that the rate of this class of error will go down with larger models trained with more data (effectively, the scaling argument). To accomplish that goal, the “robot data gap” will need to be closed, which will take a lot of compute for data generation and training larger models due to the large dimensionality of the sensory and action spaces in robotics.

It is also relatively more difficult to “scale-up” in robotics for several reasons. First, latency and real-time reaction is much more important than in a chatbot setting, and so increasing model size at the cost of latency is not viable. In Figure’s Feb 2025 blog post, we can see that a 7B parameter VLM is used, at a time when when much larger (and presumably more accurate) models were available, and 1x states that 11 seconds of thinking are required for 5 second tasks. Second, as Chris Paxton has written about many times, getting diverse and useful data to feed a larger model has a lot of challenges. Third, robots need to carry their own battery packs, and so adding a larger GPU to run larger models introduces runtime and thermal management concerns.

On the other hand, the architecture (albeit with many details glossed over) seems to be consistent across many tasks and does not require too many architectural decisions to be made or parameters to be tuned (except for training metaparameters). It also allows for a myriad of types of demonstrations to be stood up quickly for garnering buy-in and support from customers or investors, which is a significant benefit. This is understandably a parallel of some of the observations that led to the scaling-based improvements of LLMs.

World models in robotics

First, we must observe that the post-training process described above will typically use simulation environments (with simulated physics) for the training process. Despite having the appearance of being model free, the properties of the simulator (which itself uses physics models) are implicitly embedded into the learned policy.3 The 2025 DeepMind paper referenced above suggests that it may be possible to prove that this implicitly captured information can be used to extract an explicit physics model after training.

So, does that mean we should put world models out of mind and learn an implicit one as needed (or not)? Well, this is a very inefficient way to learn physics equations and parameters: Euler-Lagrange equations, and classical system ID or adaptive control methods may be able to capture the same model much more easily and in a way that is more easily generalizable. RL in general can require a large amount of training for the results they produce because rewards are typically sparse. In other words, an RL-trained policy possesses “a lot of knowledge, and in some ways far more than most, if not all, humans,” to have human-level performance on specific task. Of course, humans rely on enormous evolutionary and developmental pretraining, encoding which into specialized structures is exactly the pro-world-models argument in the debate.

In terms of the models themselves, for tasks like locomotion, Newtonian physics is very well understood, and roboticists have been building on it to develop and use models like ZMP, LIP for decades. For more abstract control systems, the concept of a “plant model” in control theory is not dissimilar to the abstract state-prediction models referred to in the section above.

Some classical methods to utilize these models are to use trajectory optimization subject to the model, model-predictive control, etc. These can impose constraints on future states, so that within the bounds of the model’s accuracy, some aspects of safety can be encoded in way that isn’t possible otherwise.

How to compare the two approaches

Now that we can recognize the “world model” debate in applications for informational and physical AI, it’s helpful to (in rough, broad strokes) know how to compare the two strategies from a number of perspectives:

Performance: Can the method produce results that are compelling? There are umpteen benchmarks to compare language models. The next generation of world-model-equipped LLMs aren’t here yet, so we’ll wait to wait a little while to see how they stack up. There aren’t robotics benchmarks of the sort yet, though some informal efforts are underway.

Scalability and time-to-market: This is a huge advantage of scaling a simple architectures. Deep neural networks with consistently-repeating matrix multiplication and reduction primitives have been able to be mapped to SIMT processors like GPUs and systolic array processors (NPUs, TPUs) with incredible performance gains. At the moment there is not even enough information about non-trivial architectures to consider mapping them to computational hardware. It is also possible that world models can be mapped into the existing computational frameworks (and we can assume that the first generation of them will have to do so to compete). Eventually, if the computations are quite different, modified paradigms and accelerators may be needed, and scaling those may require more care and thought than the straightforward process we have followed for scaling LLMs. Based on the current state of language models and humanoid robotics as recapped above, it is clearly easier to get initial proofs-of-concept working with model-free approaches scaling a simple architecture.

Computational efficiency: Newton’s equations descibe motion of bodies with very few parameters in great generality, and it is impractical to capture them with a “transformer-like” structure without significantly higher number of parameters. This is especially true where equations are discontinuous, which happens in robotics problems like locomotion and manipulation. AI is currently up against the so-called “memory wall” due to the fact that these models need to be so large, and the most recent innovations and movements in ML accelerators have been to do with addressing it. Utilizing appropriate models with differently-architected communications may completely sidestep this memory wall, as well as drastically improve the efficiency4 of equivalent computations.

Generalization: It should be clear that some of the models that need to be learned for robot motion have very applicable and general models that have been known for centuries, and the same holds for biologists, cognitive scientists, and psychologists in their fields. Ilya Sutskever, one of the architects of the current LLM era, says that their structure is weak at generalization and that generalizing in the way that humans can needs new architectures. The aforementioned DeepMind paper also cites domain adaptation and generalization to unseen tasks as something that could be improved by using world models.

Safety: We’ve discussed hallucinations in this post already, and the aforementioned Quattrociocchi paper makes an argument about the reliability of results from LLMs. The point of concern is how the system will react to unseen circumstances and whether it can extrapolate in reasonable ways. It may be especially important to have mechanisms for guaranteeing the possible range of actions the robot can take and explaining its decisions.

I didn’t feel like there is sufficient information to score the approaches yet, but it is clear that model-based approaches may offer advantages in generalization and interpretability, while model-free scaling currently dominates in deployment speed and tooling maturity.

Closing thoughts

Before closing out this article, I must point out that this “divide” is really a spectrum—there is likely a rich space of hybrids of the two approaches, which may consist of hierarchical structures combining the strengths of each. Deep learning excels at parsing and summarization of text and images, automatically finding the most appropriate dimensional reduction techniques. World models, when coupled with methods that know how to use them, are strong at generalization, abstraction, and can produce very computationally-efficient algorithms.

In future posts, I plan to write about any new developments on the informational or physical sides that are demonstrating usage and adoption of world models, or of new hybrid architectures. I will also be plan to write some posts where I construct simple scenarios to fairly evaluate competing architectures along the different metrics above. Last but not least, I will plan to go into more details on computational hardware acceleration of non-trivial architectures.

I believe this is going to be an ongoing recurring topic in this publication, so make sure to subscribe and share if you found this interesting.

The underlying transformer has seen performance-related tweaks such as GQA, and more recent “mixture of experts” models create a bit of a tree-like structure by combining different models. Also, it can be argued that tool and code interpreter usage by LLMs constitute a neurosymbolic architecture. However, it is fair to say that all these tweaks don’t represent the headlining scaling strategy for leading AI companies.

In this context, I believe the post-training component is likely to be reinforcement learning (RL) in simulation—a similar approach was used to train post-train early LLMs, and is now enhanced with a multistep process, though pure RL is still used in some applications.

In fact, “differentiable simulators” are increasingly used in RL to allow gradient-reliant training algorithms to work more easily. This is an interesting topic that we will explore more deeply in a future post, so stay subscribed for that.

The energetic cost of DRAM access is orders of magnitude higher than a multiply-accumulate operation. Systolic architectures require fewer accesses to multiply a whole matrix than conventional scalar architectures, but with the architecture being equal, fewer weights and smaller models would undeniably reduce computational energetic cost.

Great overview — I really appreciated the thoughtful comparison between scaling in LLMs and recent trends in robotics / physical AI.

This resonates strongly with patterns we’ve seen repeatedly in semiconductors over the last 20+ years. “One size fits all” compute tends to break down once you hit hard real-time loops, tight power envelopes, and latency/jitter constraints — especially in embedded systems.

GPUs (and NVIDIA’s ecosystem in particular) will clearly dominate for a long time due to tooling, legacy code, and scale, but historically we’ve seen specialized solutions emerge around the edges where general-purpose architectures struggle. Curious how you see this playing out as perception and control loops get tighter.

This is a really detailed post, Avik. I'm quite new to this, so this might be a naive question: are world models being built as foundation models + some domain/environment specific post training/fine tuning? I'm trying to draw a comparison between language models which have one foundational model like GPT, but many domain specific implementations that use the foundation model.