The architecture behind “end-to-end” robotics pipelines

Part 1: Where the learning stack ends and the control stack begins

This article is part of a series on end-to-end robotics pipelines:

This article

Coming soon

Recent progress and excitement in humanoid robotics are largely driven by rapid gains in generalist capabilities. Historically, most robots were engineered for narrow, well-defined tasks. The current wave of companies, in contrast, is pursuing systems intended to operate across a broad range of activities, shifting both public and economic expectations toward robots that can serve as general-purpose physical agents.

A central part of this shift is the widespread claim of end-to-end pipelines, often described as going from “pixels to actions,” in contrast to earlier approaches built from hand-designed perception, planning, and control modules. This post examines what “end-to-end” means in practice: where the pipeline actually begins and ends, the tradeoffs between different architectural choices, and how the algorithms map to computing hardware.

Part 1 focuses on the “actions” side of “pixels to actions”: how learned systems interface with the physical control of the robot body. Part 2 will examine how these architectures adapt to environmental uncertainty and contact-rich interaction. Later parts will include hands-on comparisons using small standalone examples to make these differences concrete.

This publication and this post contain the author’s personal thoughts and opinions only, and do not reflect the views of any companies or institutions.

Why “end-to-end”

Classical AI was built up from a strict idea of separation of sensing, planning, and action. To my knowledge, the first robot to embody Sense-Plan-Act was Shakey the robot (~1970), which also employed one of the first symbolic AI systems. This tiered structure was so formative to robotics research that most research labs today are dedicated to different portions of this hierarchy, such as “perception”, “planning”, or “locomotion”.

The sense-plan-act view today is dying a very rapid death. The modern narrative of general-purpose robotics holds that modular pipelines often fail because of limitations imposed by this decoupling; for example, perception errors break planners, planners produce infeasible motions, and most importantly, interfaces encode wrong assumptions.

As influencial AI researcher Sergey Levine puts it,

for any learning-enabled system, any component that is not learned but instead designed by hand will eventually become the bottleneck to its performance

End-to-end training avoids hand-designed intermediate representations, manually tuned cost functions, and any bottlenecks imposed by module interfaces.

Additionally, “end-to-end” sends a sociological signal to do with modern AI foundation-model alignment, scalability with data, and positions the company as an AI lab instead of a controls shop.

The action end in practice

The practical reality of “end-to-end” is more subtle than it might seem. In this section we’ll review what some published academic and commercial implementations actually appear to be doing today, and also try to outline how the implementation is mapped to computational hardware.

The old way: model-based stacks (~2014)

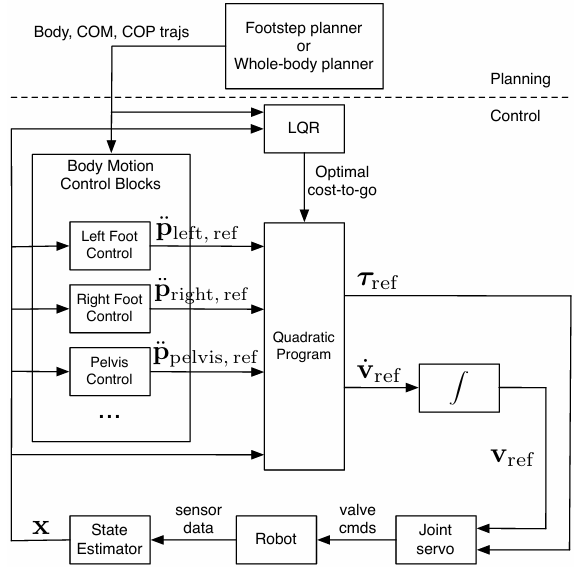

It is very common to have a whole-body controller at the low-level, as exemplified by the 2014 MIT Atlas team’s report. After a high-level plan is created, a tracking controller is implemented as a quadratic program, and that generates the signals sent to the actuators:

Mapping to computational hardware:

Trajectory optimizer (CPU) → WBC inverse dynamics/QP (CPU) → Joint/servo controllers (microcontroller/CPU) → Torques

Learning followed by impedance controller (~2017-2020)

To my knowledge, the first fielded robots using learning-based locomotion controllers appeared ~2018 from Google (using Minitaur) and in Marco Hutter’s group. As documented in the 2018 paper from Google and the highly-cited Hwangbo et al (2019) paper, the most effective choice of action space was an impedance controller in turn influenced by Peng et al (2017):

Our experiments suggest that action parameterizations that include basic local feedback, such as PD target angles, MTU activations, or target velocities, can improve policy performance and learning speed across different motions and character morphologies

The policy outputs desired joint positions and sometimes velocity offsets or gain modulation, and the torque applied is a simple algebraic equation:

The virtue of this architecture is that it is very generic, and succeeds in decoupling the fast time-scales and discontinuities of making and breaking contact from the learning algorithm.

Mapping to computational hardware:

Policy eval (CPU/embedded GPU) → Impedance controller (CPU) → Actuators

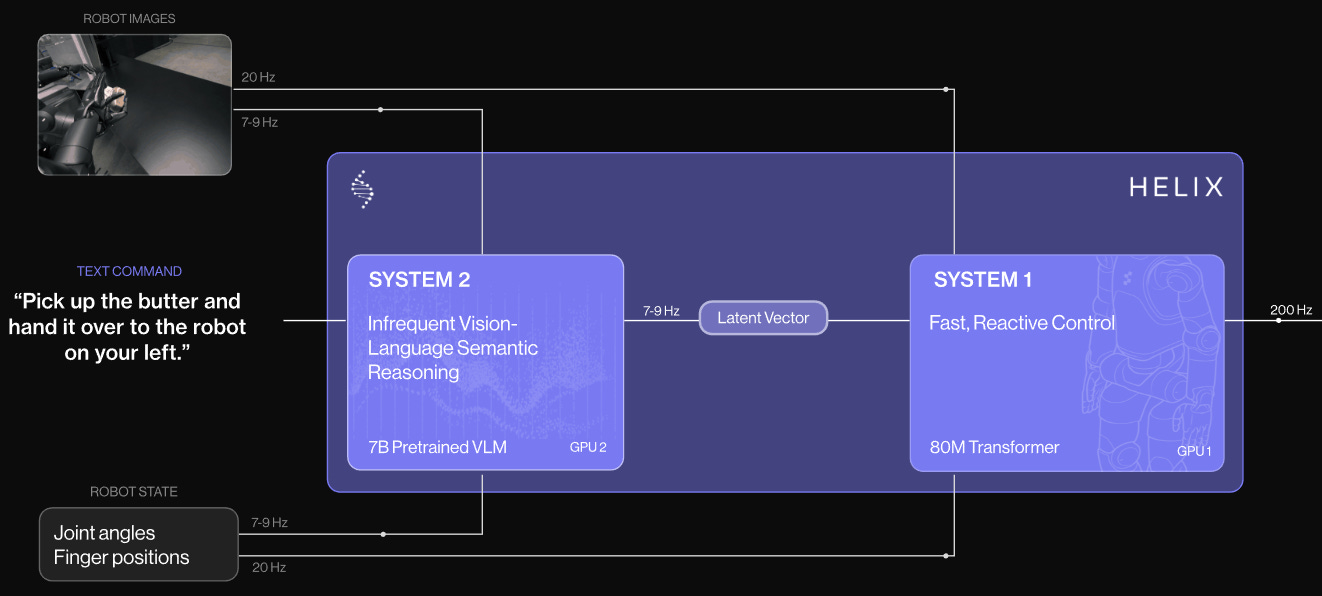

Figure AI’s “System 1” policy (2025)

Figure AI’s Feb 2025 blog post describes a “System 2 / System 1” design where a high-level vision-language model (S2) reasons about goals and semantics at low frequency, and a fast visuomotor network (S1) executes continuous control at high frequency. While this reflects a separation of timescales and roles, both modules are trained end-to-end with an abstract latent interface, meaning there is not a principled, physically interpretable handoff between high-level strategy and low-level control. As a result, Helix achieves generalization in perception and task reasoning but does not isolate physical control concerns (such as dynamics stabilization, contact interaction, or actuation abstraction) into structured model-based or classical control modules.

In a Mar 2025 blog post, they describe what sounds more like the impedance controller above than the system 1 design, so it’s possible some combination of both architectures is utilized:

We additionally run the policy output through kHz-rate closed-loop torque control to compensate for errors in actuator modeling

Mapping to computational hardware:

System 2 (Transformer, GPU) → System 1 (Network, GPU) → [Impedance control (CPU)] → Torques

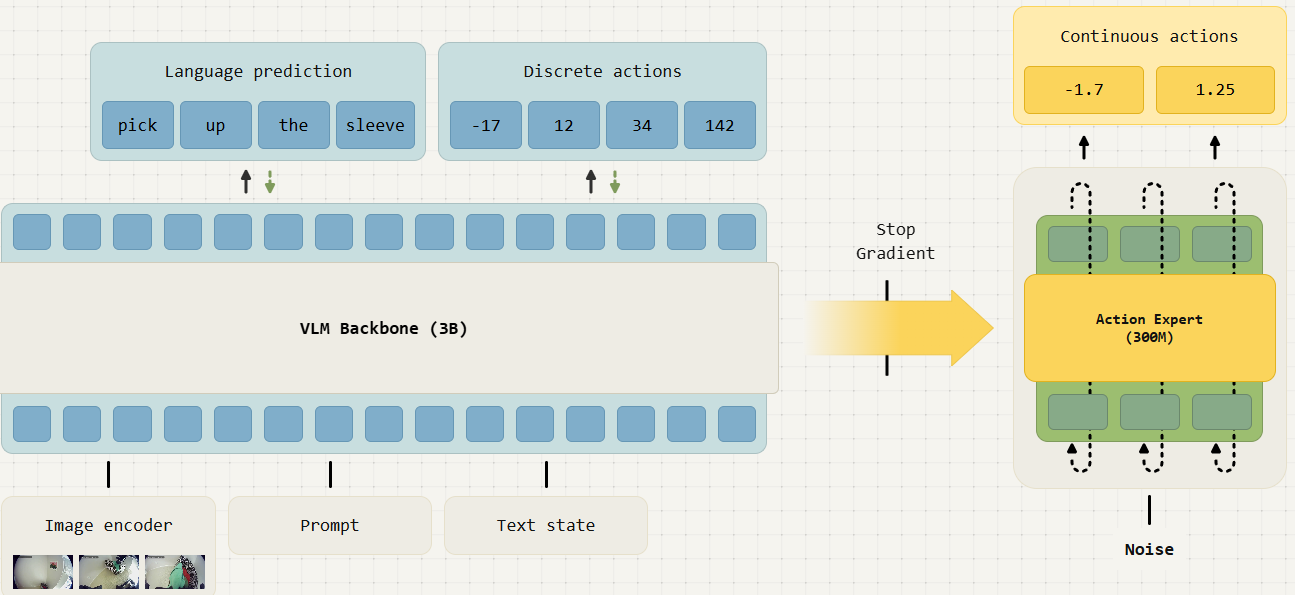

Physical Intelligence’s action expert (2025)

The architecture described is similar to the system 1 above, but specifically suggests that the end-to-end training causes problems:

When adapting a VLM to a VLA in this action expert design, the VLM backbone representations are exposed to the gradients from the action expert. Our experiments show that those gradients from the action expert lead to unfavorable learning dynamics, which not only results in much slower learning, but also causes the VLM backbone to lose some of the knowledge acquired during web-scale pre-training.

This is conceptually analogous to known problems like vanishing/exploding gradients in deep nets, where lower layers dominate or drown out meaningful gradients for higher layers.

Another blog post describes issues to do with the mismatched control bandwidth of foundation model output to robot dynamics, solved by outputting short horizon trajectories that are played out by a low-level controller.

Mapping to computation:

VLM (GPU) → Action expert (GPU/CPU) → Trajectory tracking (CPU) → Torques

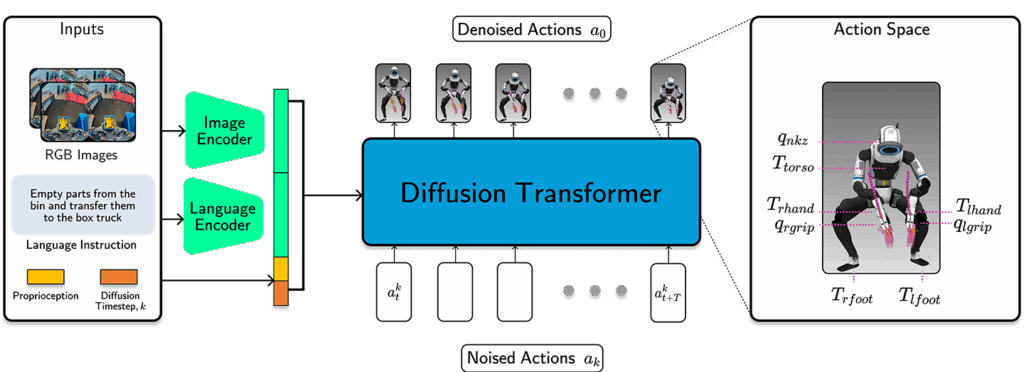

Boston Dynamics + TRI’s pose tracking (2025)

Their blog post describes an architecture with the higher-level cognitive layer outputs joint positions and end-effector poses. While there isn’t an explicit decription of how these position setpoints are tracked, the post mentions Atlas’s MPC, and it is reasonable to assume that that is the lower-level controller.

Mapping to computational hardware:

LBM inference (GPU) → MPC (CPU) → Actuator torques

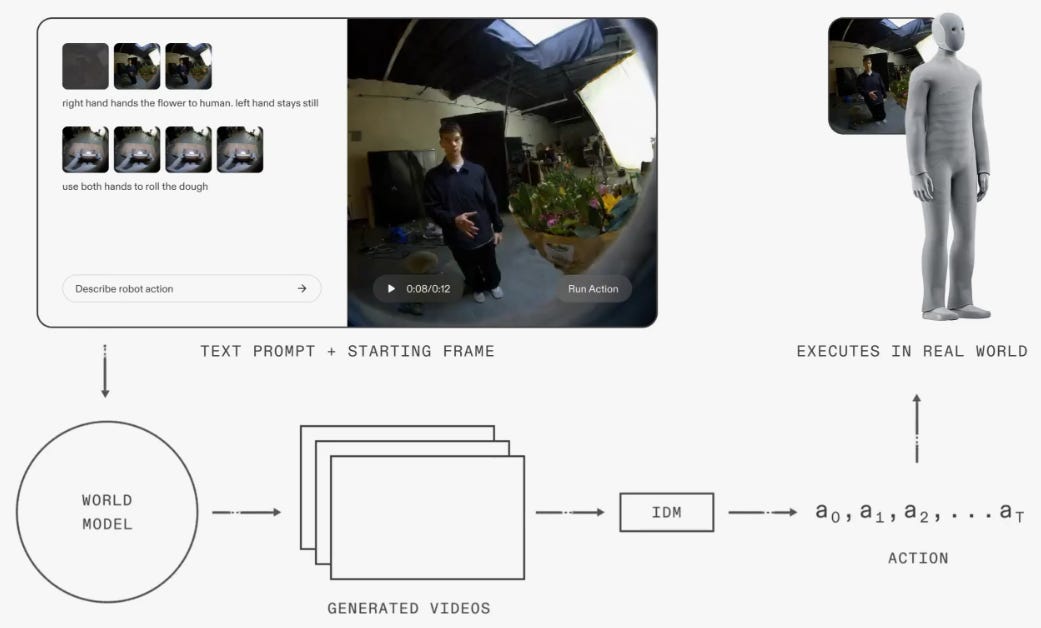

1X’s inverse dynamics model IDM (2026)

1X also describes a hierarchy in their blog post:

World Model Backbone (WM): A text-conditioned video prediction model trained on internet-scale video data and fine-tuned on robot sensorimotor data. It predicts future visual states based on current observations and candidate actions.

Inverse Dynamics Model (IDM): Converts predicted future states into feasible robot action sequences that will produce those outcomes in the real world. The use of the term “inverse dynamics” suggests that the output actions are torques, though that isn’t specified.

Mapping to computational hardware:

World model (GPU) → IDM (GPU) → Actuator torques

Why not end-to-end

From the previous section, it is apparent that “end-to-end” doesn’t usually mean that a single algorithm or network is going from pixels to torques. In this section, we’ll try to list some potential intuitive reasons for this.

Separation of concerns

We saw above on Physical Intelligence’s blog post that there are difficulties in training an end-to-end policy that does so many different things. Another quote:

One hypothesis of why this is happening is the following. A pre-trained VLM, by its nature, pays attention to language inputs well. The gradients from the action expert now severly interfere with the model’s ability to process language, which leads the model to pick up on other correlations first.

These problems are a side-effect of one network trying to solve a lot of different problems. The old Sense-Plan-Act schema enforced a separation of concerns very strictly, but even with a more relaxed architecture, low-level control priors drastically reduce the policy search space.

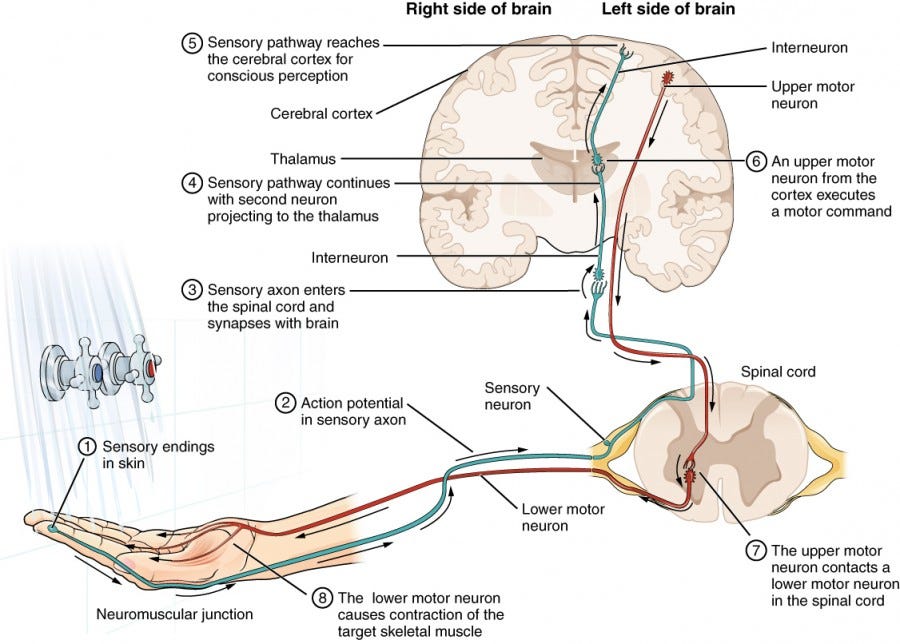

A human nervous exhibits similar separation with a cortex (goal-directed commands), cerebellum (fast adaptation, prediction), spinal reflexes (fast control loops), and even mechanical impedance control in muscles / tendons.

Training complexity

Related to the separation of concerns above, an end-to-end network must learn contact mechanics, actuator dynamics, delays, friction, impact stabilization, as well as task-level planning, all in one gradient signal.

This creates extremely long credit chains and high sample complexity. Hierarchical control factorizes the learning problem.

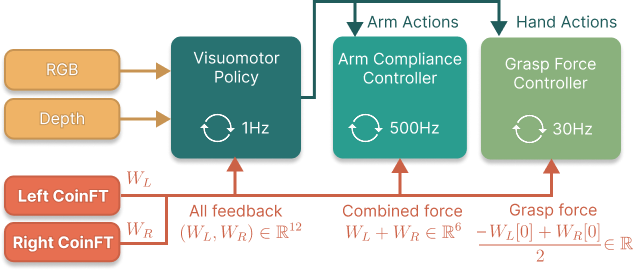

Feedback control loops; tactile and force feedback

With a fully end-to-end system, any feedback on how the executing is going can only come in at the top. In contrast, a dedicated low-level control unit can run its own feedback controller that performs stabilization functions. This is in effect what we saw above with the selection of the impedance controller in the Peng and Hutter papers above.

Secondly, a low-level controller also provides a great opportunity to incorporate a rich set of sensory signals such as tactile and force feedback information. Rodney Brooks underlines the importance of non-visual feedback in his Sep 2025 essay, going as far as to flag it as a roadblock. The problem is, if you must have force feedback in an end-to-end model, you first have to contend with the lack of large-scale force data to train it from, as well as the much larger end-to-end model you now have to train and evaluate at inference-time. As I responded to a Substack comment here, a low-level control unit is a potential way that that data could be incorporated, without increasing the dimensionality of the higher-level brain.

Control bandwidth

Real-world physics and dynamics don’t wait for end-to-end inference to complete, and most implementations (Physical Intelligence’s action chunking, Figure’s rate-decoupled system 1, etc.) need to decouple the control bandwidth of the cognitive layer from the low-level controller.

Chris Paxton talks about this aspect as an action inference limitation in his excellent post about VLA’s which you should read if you haven’t.

Sim2real transfer

As discussed in my recent world models post, almost all these implementations that utilize large-scale demonstration data need to follow it up with reinforcement learning post-training in simulation. This surfaces an issue that has been named “sim2real transfer,” where the simulator’s accuracy can limit the deployed behavior. This has a number of solutions including domain randomization and actuator networks, but alternatively, having a low-level controller can in many cases absorb modeling error with their inverse dynamics functionality. Physics errors affect torque-level policies massively, but impedance control, whole-body control, or model-predictive control absorb modeling error by actively driving mismatch errors to zero.

Safety constraints

We can explicitly add torque constraints, joint kinematic limits, self-collision avoidance, to a low-level controller. This is intuitively true, but I’ll leave an example of a recent research paper which found out exactly this. Quoting the author:

Introducing UMI-FT: the UMI gripper equipped with force/torque sensors (CoinFT) on each finger. Multimodal data from UMI-FT, combined with diffusion policy and compliance control, enables robots to apply sufficient yet safe force for task completion.

Generalization across hardware embodiment (*maybe)

In principle, if the low-level controller completely abstracts the hardware, the higher-level brain’s functionality can be kept the same with different embodiments. Intuitively, you can reuse high-level policies if low-level layers abstract hardware, and you can improve low-level stability without retraining ML.

However, this intuitive point is difficult to verify due to the methodology of how the cognitive models are developed today. The end-to-end pixel → action policies always incorporate some amount of information about the embodiment, so it isn’t possible to train an abstract cognitive model. In practice, the foundation models of today train on cross-embodiment data to obtain generalizable knowledge. To get to the bottom of this facet, we would need to understand what constitutes a cognitive model separate from embodiment, and that is not known yet as discussed in my previous world models post:

Closing thoughts

With the end of Sense-Plan-Act, the new robotics north star is an end-to-end pipeline that does away with the need for any task-specific pipeline architecture or programming. However, today’s successful implementations tell a different story, and there are a number of intuitive reasons for this.

Foundation models excel at semantic, perceptual, and strategic reasoning, but they are mismatched to high-bandwidth, stability-critical motor control. A robust robotic architecture separates concerns into layers aligned with physical timescales and modeling regimes.

In this (part 1) article, we focused on standard visuomotor task execution. In part 2 of this series, we’ll look at how unexpected events and motor adaptation are handled in these architectures. After that, to continue this series, I’d also like to explore a standalone demonstration that can be published as an open-source repo that examines a few of these architectures and compares them fairly.

If you found this post interesting, please let me know in the comments, and share, and subscribe. Thanks for reading!

Excellent post. For the open-source component, will you only be comparing what you call end-to-end methods? Or will you also have some classical/hybrid baselines as well?

This is a great post, I especially liked the clear hardware mapping for each example.

This may be an oversimplification, but from what I understand, there seems to be a clear split between two layers - planning and control.

Planning seems to be "heavy compute, low frequency" - like running VLMs or a World model on a GPU. Control seems to be more lightweight, but needs higher frequency, hence mostly running on CPUs.

So is it realistic to expect a hybrid architecture with some, or all of the planning to move to "the cloud." I know that some applications cannot tolerate the unpredictability of cloud latency, but there could be many applications where it could be fine - like robots in a controlled factory environment. If this is realistic, then the hybrid architecture might be better economically (by sharing compute for a group of robots) and might also make the robots lighter + power efficient.

Do you think that's a viable direction for robotics?