What von Neumann understood about the architecture of intelligence before we built AI

The Computer and the Brain anticipated both the successes and shortcomings of deep learning AI 70 years ago

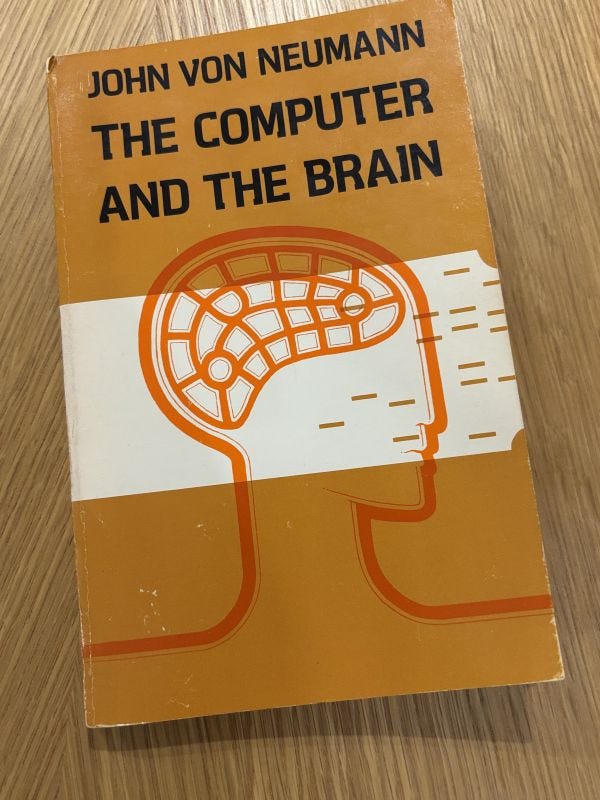

My weekend read was “The Computer and the Brain”, an out-of-print book I picked up at the Strand Bookstore last year. John von Neumann wrote most of the contents in 1955 to prepare material for the Silliman lectures in 1956—an obligation that clearly meant a lot to him. He was diagnosed with bone cancer that year, but continued writing his notes in the hopes of being able to deliver them in some form. Tragically, he was never able to deliver the lectures, but his wife was able to collect and publish the partial manuscripts prefaced by a heart-wrenching letter, and they would become his last words on these topics.

I’ve known of von Neumann’s huge legacy on modern computing from a college computer organization course, but I was stunned at how much he was able to extrapolate into ideas about computation in general. His writings, from before the first transistor-based computer was built, are ever-relevant after 70 years of exponential growth in computing technology. He wasn’t correct about everything—that would be impossible—but the ways in which he was wrong are even more revealing and thought-provoking. They anticipate the reason deep learning has been so capable, and also predict the architectural limits we are now running into—memory bottlenecks, brute-force scale, and energy-hungry intelligence. They also anticipate the future directions we can go in to overcome these deficiencies.

The book is very short and absolutely worth a read if you can pick it up from a library or used bookstore, but I had four broad and powerful takeaways that contextualized decades of development for me.

Scale & memory: Basic operations force massive memory movement

Precise vs. statistical: Deep learning (DL) escapes numerical fragility by becoming brain-like

Depth vs. architecture: DL substitutes scale for structural sophistication in the brain

Representation & substrate: DL is rigid where the brain is fluid

I’ll explain these four aspects below, but together they point to the same overall thesis:

Modern AI succeeded by replicating the statistical aspect of natural computation, but suffers from brute-force scaling inside an architecture that von Neumann already suspected was fundamentally mismatched to cognition.

1. Scale & memory

As the book says, the principle of “one organ for each basic operation” necessitates memory for intermediate values, on top of instruction and data memory. Von Neumann predicted that computation systems built from simple primitives can only scale by also scaling memory.

Scalar CPU architecture is still very close to von Neumann’s artificial automaton. Post-von-Neumann architectures include systolic arrays (TPUs) and near-memory compute; GPUs are a bit of a hybrid with shared memory (scratchpads), and tiled matrix multiply (data reuse). Even heavily optimized post-von-Neumann machines are still dominated by data movement, because the algorithmic structure forces it.

Modern deep learning vindicates this: intelligence is achieved not through complex operations but through scale, which makes memory movement, not computation, the central bottleneck of contemporary hardware. We have been talking about the AI memory wall for a few years, but it was inevitable from these predictions 70 years ago.

A related aspect which von Neumann couldn’t have anticipated was the energetic impact of memory access. He did write about the energetic cost of logic operations, but today, moving 1 bit from DRAM costs more energy than 1 FLOP, to the tune of 100× a multiply. This pressure is driving technology development in near-memory compute, in-memory analog MACs, optical interconnects. The same architectural tension von Neumann identified today drives the economics1 of AI hardware.

2. Precise vs. statistical

One of the central topics in the book is how digital computation needs very high precision because of the high arithmetic depth of repeated basic operations. If each operation has error ε, after N steps you expect error ≈ O(Nε). Deep networks have extreme arithmetic depth with thousands of layers and trillions of operations. However, empirically, 4-bit quantization in deep learning works with nearly no drop in accuracy.

Why doesn’t error compound the way von Neumann predicted?

The key: von Neumann analyzed precise numerical methods (like solving equations, integrating trajectories), but neural networks are different in a couple of important ways:

Noise is inherent in the training process, resulting in a function approximator with inherent robustness to input noise.

In the accumulation function, the errors are mixed across thousands of dimensions, clipped by nonlinear saturating functions, and averaged out statistically.

The overall error is clamped and damped, and does not propagate in the same way that von Neumann assumed.

Relatedly, von Neumann argued that the brain works with low precision (1-10 bits), and performs a different type of computation than digital computers (32-64 bits). He referred to the brain as performing “statistical computing”. So deep learning is not violating von Neumann, but it is occupying the biological side of his dichotomy.

3. Depth vs. architecture

Von Neumann emphasizes three biological facts about neurons:

Low precision

Low speed (~10 ms per spike, though they can respond slightly faster under extreme stimulation)

Shallow circuits

We discussed the precision above; let’s dig into the others next. The nervous system is very slow, with each “layer” taking on the order of 10 ms to fire and reset (compared to digital lines changing state in < 1 ns). This means that while it is feasible to have a “deep” digital computation, that would be infeasible in a natural system.

The shallowness is also important: a crucial example in the book is that the retina does significant computation using three synapse layers, which is orders of magnitude smaller than is needed for modern Vision Transformer (ViT) encoders (hundreds of layers, billions of parameters).

How is this possible? The answer is that a biological neuron is not a basic linear unit + nonlinearity; it is more like a small analog computer. Each neuron has temporal dynamics, neuromodulators, and plasticity rules. Its connections are even more complex: each has hundreds of synapses, nonlinear integration of activations with potential spatial and geometric relations.

So the contrast is stark:

The brain has shallow compositions of slow and low-precision units

Deep nets have very deep compositions of very fast and medium-low-precision units

Von Neumann predicted that these fundamental differences in the basic blocks would result in different natural vs. artificial computing paradigms:

Hence the logical approach and structure in natural automata may be expected to differ widely from those in artificial automata.

Modern deep learning compensates for architectural simplicity with scale. Biology compensates for slow, noisy hardware with architectural sophistication and better primitives. This distinction strongly influences why our systems are large, power-hungry, data-hungry, and memory bound.

I hadn’t anticipated this connection when I started reading the book, but my article from last week also visits this architectural distinction from a world-model-representation perspective:

Why did we choose scaling of simple units for computing? Among other reasons (as discussed in the previous article), deep learning was built around universality + scalability, not biological realism. Simple units have advantages: easy to parallelize, easy to implement on GPUs, and easy to map to silicon.

What does this mean for general artificial intelligence? Von Neumann suspected that digital logic gates were too primitive to model cognition efficiently, and with today’s technology it is certainly true that the brain’s performance at 10W cannot be matched even at much higher power.

4. Representation & substrate

Von Neumann observes that representations of quantities which go through the nervous system may change from digital to analog and vice versa repeatedly. They can also have adaptive precision representations2. In contrast, digital machines commit very early to fixed-width numbers everywhere (FP32, FP16, INT8, etc.), and even “mixed precision” is coarse and static.

These points seem to suggest another architectural dichotomy (not just the connections between units, but also in how numerical quantities are represented). The brain has adaptive primitives, precisions, and numerical representations, whereas they are all fixed in the digital computing paradigm.

Is the answer analog computing? Von Neumann himself rejected naive analog computing due to its problems of scalability and reliability. The brain may be powerful while being efficient because it is representationally flexible, not because it is analog per se.

Neuromorphic computing is exactly about this axis, with conceptual departures such as event-driven computation, mixed analog/digital circuits, co-located computation and memory. My knowledge of the field is limited and I am not sure that any of the existing research in that area truly captures what von Neumann was hinting at, but I suspect that in the long-term future of this publication, neuromorphic computing will come up again.

Thanks for reading! Let me know if you’d suggest any related historical or modern writing on this topic, and please share and subscribe if you liked the essay.

See, for example, Groq-NVIDIA deal, DRAM shortages.

A nice example of this is the “average pulse frequency” interpretation of a sequence of quasiperiodic pulses. Coarse spike counts suffice for rough decisions, and temporal averaging increases accuracy automatically.