Using models to design a RoboBee

Paper in IROS 2020 about using templates and optimization for robot design

While there have been numerous projects where I’ve utilized reduced-order models for control, this is the first published1 one where I’ve been able to use them for optimizing robot design. It is also applied to a fairly complex system, the RoboBee, justifying the effort expended into developing numerical methods for design.

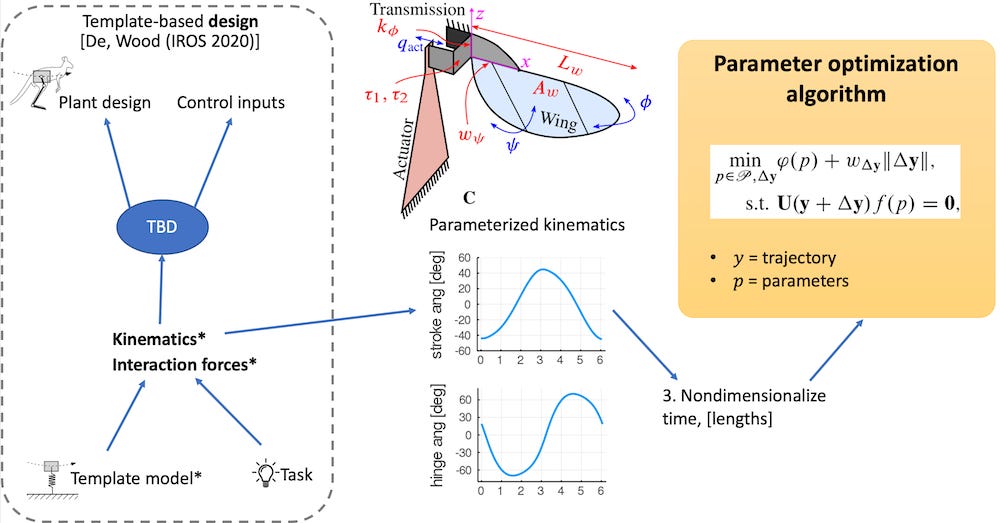

System architecture

The starting points for this method are a template model, and a task. In this case, the task is flapping, and the model is the blade element model applied to flapping wings. Those two, in conjuction give us a dynamical trajectory, with kinematics and interaction forces with the environment.

These kinematics are obviously parameterized by the parameters of the model that generated them. For example, if a flapping wing has more inertia, we can expect a smaller angular amplitude when subject to the same flapping torque.

For our design optimization, we non-dimensionalize the times and lengths in the trajectory. With this non-dimensional trajectory y(t), and a parameter vector p, we utilize the fact that in mechanical systems, the dynamics are affine in p, i.e. the dynamical equations of motion can be written in the form

This fact underpins classical adaptive control, and in our case here, allows us to establish a bilinear constraint between state and parameter variables.

So, the design optimization problems attempts to find paramters that can minimize energy consumption, or another objective specified in ϕ(p), while minimizing the deviation from the desired trajectory ‖Δy‖, and constrained by the system dynamics.

Nonlinear transmission design

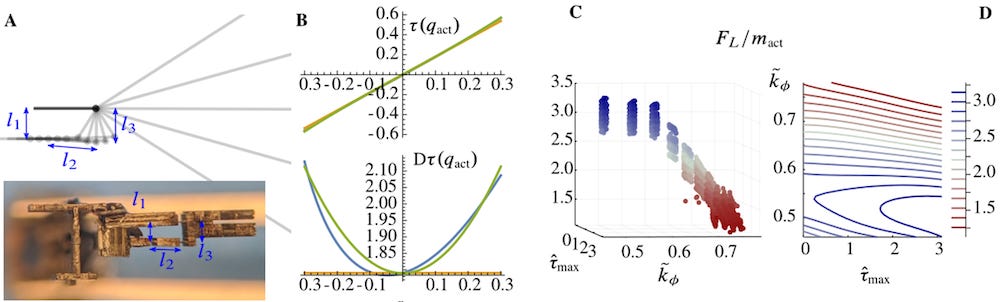

The main empirical contribution of this paper was a new type of transmission I designed for the RoboBee (A in the figure below), where the transmission ratio varied as a function of the actuator angle.

The green line in B shows an ideal nonlinear transmission (with ratio τ=τ1+τ2qact), and the yellow/blue lines show the physically realizable transmission developed using a non-parallel linkage system for this paper.

Intuitively, the goal was to have a lower transmission ratio (higher mechanical advantage) at midstroke, where the drag force is the highest, and higher transmission ratio (lower mechanical advantage) at the end-stroke positions where the drag force is lower.

C/D in the figure above show the simulated results of using such a nonlinear transmission – the specific lift force (normalized by actuator mass) can be increased using this kind of nonlinearity.

Co-design pitfalls

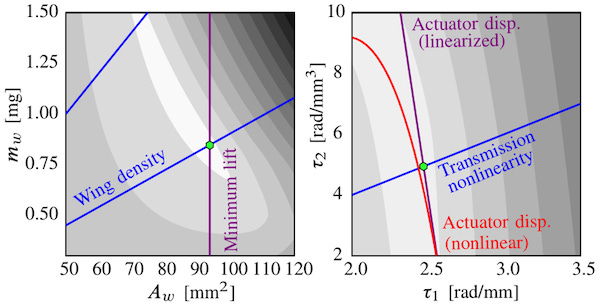

The bilinearity in the constraint above exactly conveys some of the difficult aspects of “co-design” (i.e. simultaneous design and control). The plots below show some slices of contours of the objective function for the RoboBee design problem with highly nonlinear level sets.

Some observations from the plot above:

The left plot shows a feasible set of wing mass (vertical axis) with respect to wing area (horizontal axis) between the two blue lines. The purple line is a minimum lift constraint needed to fly, for which a minimum wing area is needed. In the top right feasible region, there is a unique optimum that was found.

The right plot shows two parameters controlling the transmission ratio between the actuator and the wings. The feasible set of transmission designs is under the blue line in this case. The red line is a constraint on the maximum actuator displacement allowed (so that the piezoelectric actuator does not break), and a conservative linearization of that constraint is shown by the purple line. The objective function is again highly nonlinear, but the design optimization is able to find an optimum that would intuitively likely have been challenging.