Approximating cyclic dynamics utilizing symmetry

Paper on Hybrid averaging (IJRR 2018)

I’ve previously written about the generative possibilities with parallel composition of reduced-order models.

Both these projects were extensions of the Raibert’s intriguing concept of “control in three parts” for the MIT Leg Lab planar hopper. However, it has been very difficult to formalize when this type of control may work. In some related work, it is called “decoupled control,” but it is clear that any robotic system of practical value will not have a decoupling property. The hallmark of articulated mechanical systems is that energy can be transferred among different components, which makes them expressive and capable, but also difficult to analyze.

In this project and paper1, we proposed hybrid dynamical averaging as a way to make progress toward making formal arguments about these complex systems. This project only scratched the surface, but we applied this idea to Minitaur vertical hopping in a sequel. I think the idea still has a lot of potential in helping us make formal guarantees about the behavior of complex systems with symmetries (ubiquitous in locomotion), maybe playing an important role in formally guaranteeing their behavior in safety-critical scenarios.

Dynamical averaging

Since the exact system dynamics are difficult to directly analyze, it’s helpful to consider approximating the behavior somehow. To this end, we looked to the well-established theory of dynamical averaging (Guckenheimer and Holmes), which applies to cyclic dynamical systems.

The idea is that a dynamical system with a limit cycle can be viewed in terms of a single “fast” coordinate along the limit cycle, and several orthogonal “slow” coordinates. As an example, an oscillating spring-mass system conserves energy, so the total mechanical energy is clearly a “slow” coordinate (it doesn’t change at all). A very slight generalization is a regulated oscillatory system, where the energy might vary as it stabilizes to its limit cycle.

These “fast/slow” dynamical systems can be approximated by averaging the dynamics along the limit cycle:

By doing this, we have reduced the dimensionality of our system by one, and crucially, eliminated any variability in f that “averages out” over a cycle. This has huge intuitive (and mathematical) implications that we will come back to below.

Choosing coordinates

The spring-mass example above conveniently was two-dimensional, resulting in a singular slow coordinate that we easily identified with total energy. What happens when there are (for example) several coupled spring-mass oscillators, with total system dimension n?

This example is instantiated in a very real manner in the Minitaur vertical hopping demonstrations, and can appear frequently in coupled mechanical systems.

Our idea here was to think about the different coordinates as being:

A single fast coordinate identified as the system phase: the cyclic coordinate that increments at a near-constant rate

A single slow coordinate identified as the system energy: an overall measure of the “amplitude” of the system

n−2 slow coordinates identified as phase differences: the relative phase of different degrees of freedom of the system

These coordinates are related to (but not being formally connected to) Hamiltonian phase space coordinates. The phase differences intuitively arise when several degrees of freedom are coordinated together, as in a set of coupled oscillators.

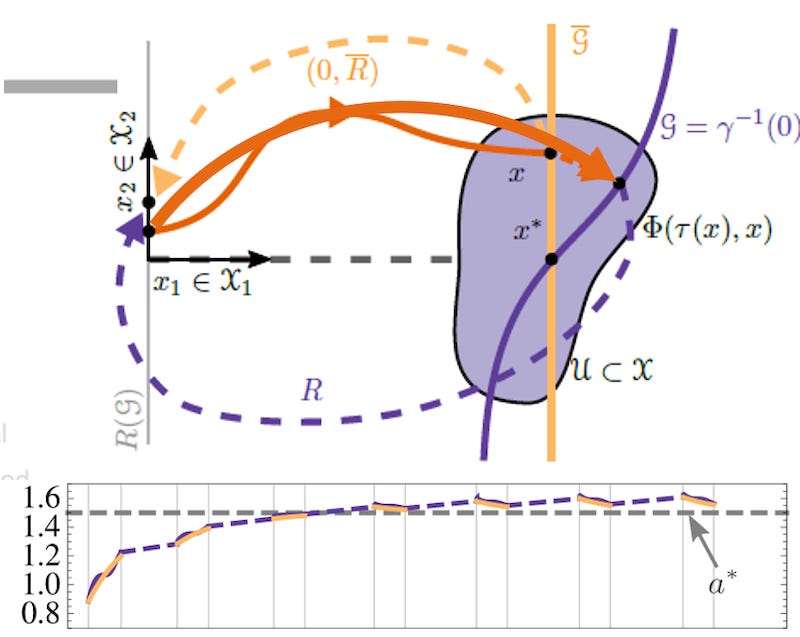

A visual depiction of these coordinates, with (n=3), is shown below, where the blue manifold corresponds to the energy zero set, and the red manifold corresponds to the phase difference zero set. We intuitively refer to these as the regulated and neutral sets:

Note that for mechanical second-order systems, (n) must be even (twice the number of degrees-of-freedom); the (n=3) is for illustration.

Hybrid averaging

The major contribution of this paper was to prove that it is possible to extend dynamical averaging to hybrid systems. To do this, we used the saltation matrix to capture the effect of the hybrid reset near the limit cycle.

A visual depiction of this is below:

A much more technical treatment and formal proof of the intuitive idea is, of course, in the paper.

Symmetries and averaging

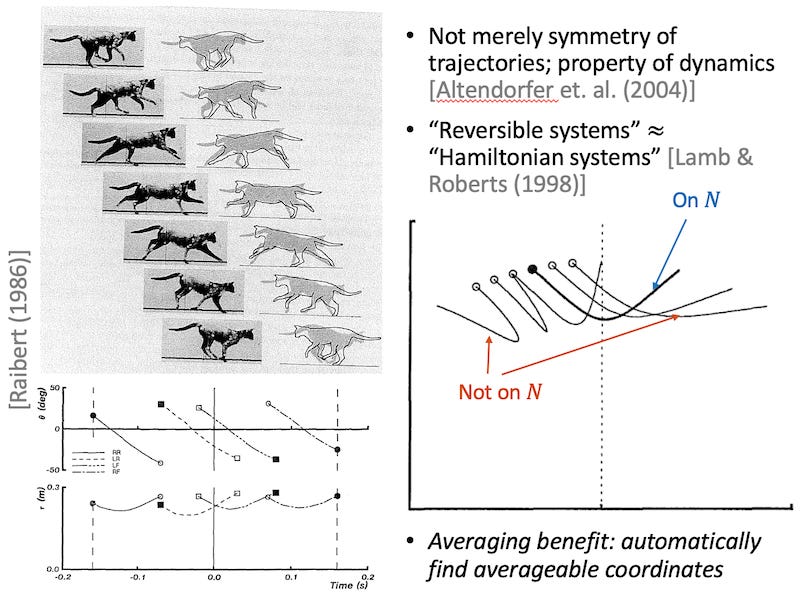

Applying (hybrid) averaging to study locomotion behaviors like hopping and running let us incorporate time-reversal symmetry to get amazing and intuitive reductions in system complexity.

First, the following slide, which some figures from Legged Robots That Balance, convey the ubiquity of time-reversal symmetry in locomotion. This is straightforward in systems like a one-legged hopper, but also appears in much more complex scenarios like a cat galloping.

As the slide suggests, the referenced symmetry is not merely a property of the resulting trajectory, but a property of the dynamics itself (i.e. the dynamics (xdot = f(x, u)) exhibits symmetry with respect to various components). This has exciting connections to Hamiltonian mechanics and Noether’s theorem that beg further exploration.

As annotated on the slide, the “symmetric” hopping trajectory in bold in the bottom right figure can be distinguished from all the asymmetric trajectories. These simply correspond to being on the “neutral” set in our nomenclature above, or not, respectively. Putting all this together, when the dynamics are averaged at a neutral limit cycle, the dynamics are greatly simplified (intuitively, odd functions integrate out), giving us a great degree of analytical simplification.