Jerboa robot reorienting, planar hopping, and hip-hop

Follow-on projects with the Penn Jerboa robot from 2016-2018

I have previously introduced the Penn Jerboa robot, developed ~2014 at UPenn.

While it was technically the first of the “family of direct-drive robots” developed during my Ph.D., the first paper that was published on the architecture featured Minitaur, as I wrote here:

Minitaur had 8 motors and 4 legs—which made it signficantly easier to program to jump, hop, walk—and so it was fair enough that it was featured in the first publication on these robots, and went on to be the first “product” that was spun out.

Nevertheless, Jerboa was morphologically significantly more interesting, and became the topic and motivation for several new directions of research. In this article, I’ll talk about a few of them that were completed during my tenure, though there were projects underway as recently as 2025.

Tailed reorientation (2016)

While most of my doctoral research had to do with walking and running using legs, in this project, we looked purely at re-orienting (like a falling cat) using a tail. This implied a few key differences from the previously discussed mobility research:

We only need to analyze a continuous dynamical system without any mode switching, i.e. it is not a hybrid dynamical system

The inputs (or actuators) available are the ones connected to the robot tail

The objective function is very simple - get the main body/torso orientation to a desired state

The Jerboa robot had the tail connected to two motors, with a transmission that meant that the torque produced in the tail actuators was larger than from the legs (core stronger than legs):

There are a number of similarities to the falling cat problem, except that cats are predominantly using their core muscles, and flexibility in their core/back instead of their tails for reorienting while falling.

As the paper1 shows, the mathematical analysis is satisfying and can be verified experimentally while free-falling, or during the aerial phase of hopping.

In both the falling cat problem and this one, the key effect is that there is a non-holonomic constraint on the system dynamics due to the conservation2 of angular momentum. An easy to understand analogy is parallel parking a car: there are no inputs that can translate a car sideways, but a driver is able to use the steering and fore-aft inputs to move into a parking spot alongside.

Pitch-unlocked hopping (2018)

The initial Jerboa hopping results constrained the pitch of the body using a “boom” (the large carbon fiber tube visible in the video):

This is because it was difficult enough to get “tail-energized” hopping to work, where a single actuator (“wagging” the tail") would controllably make the robot hop up and down as well as translate forward and back.

It took a few years to remove those guardrails and free the body pitch. After this project, there is still a carbon fiber tube, but it is only constraining the robot in a plane.3

The solution that we published4 was, of course, to add more bottom-up controllers working in parallel. This path had been clear since the initial Jerboa publication:

Still, a lot of work had to be done to optimize the tail and leg design, as described in the paper, and to tune the behavior:

Hip-energized hopping “hip-hop” (unpublished)

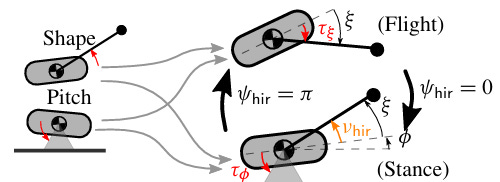

As shown in the cartoon above, the initially-imagined Jerboa robot hopping behavior allocated5 control inputs to degrees of freedom as follows:

Tail in stance → height

Hip in stance → pitch & tail position (“shape”)

Tail in flight → pitch & tail position (“shape”)

Hip in flight → reposition leg

Is this the only “allocation”? One idea for an alternate was:

Tail in stance or flight → pitch & tail position (“shape”)

Hip in stance → height

Hip in flight → reposition leg

The key difference was that the legs would “power” the locomotion, which is an intuitive concept from the perspective of a tail-less animal. I developed some simple feedback controllers and showed in simulation that this could work, but it was very sensitive:

On the robot, the experiments were even more primitive, and I had to use the tail as a kick-stand to poke against the ground to stabilize the body pitch:

As an aside, this is a consequence of my favorite result from physics, Noether’s theorem.

There is a long tradition of “planar hoppers” constrained/supported as such, e.g. Raibert’s planar hopper.

This is once again inspired by Raibert’s “control of hopping in three parts.” Modern optimal control or learned methods will not have these allocations, instead leveraging all possible actuators at all times. Our idea during my thesis was to explicitly not do that, with the advantage of keeping controllers low-dimensional and modular. Does this make sense today as computation gets cheaper and more powerful, or is it pointless? Let me know in the comments!