Power-efficient and safe mobile robots

Talk at OSU CoRIS seminar

I gave a talk at OSU’s CoRIS seminar. It was a joy to visit OSU’s Robotics department. The faculty are driven to solve problems grounded in the real world, in application areas ranging from under the sea to the peak of Mt. Hood. Also, it was only partially raining on the day of the seminar (which I found out was a rarity).

Modularity

In this talk, I started a bottom-up exploration of composition in robotics.

Dynamic legged locomotion

As with I’m sure many others, as a young graduate student, I was inspired by the dynamic legged locomotion work at the MIT Leg Lab in the 1980’s:

In his thought-provoking book, Raibert articulated an intriguing idea called “Control of Running Decomposed into Three Parts.” Researchers have been trying to understand when and how this may be possible, and how it generalizes, since then.

My Ph.D. advisor, Koditschek, has been doing that for decades. In the 1990’s, his research group built and impressive array of juggling robots (as a less-power-hungry proxy for cyclic dynamical behavior):

In the course of the juggling research, they introduced a formal idea of sequential composition with an intuitive but mathematically rigorous and useful idea:

Analogously, we can retroactively label Raibert’s “control in three parts” idea as an example of parallel composition. While the term is not extremely common in the robotics literature, similar concepts appear with names such as “decoupled control”. The idea has clearly been empirically useful, but formalizing it has been quite tricky with any degree of generality.

Sequential and parallel composition are a very intuitive idea with equivalents in programming and spoken language. Consider the example of generating spoken language – instead of outputting the sounds corresponding to an entire sentence at once, we may want to start by assembling words from phonemes, and assembling those into sentences. On the other hand, modern deep learning speech synthesis may not have any such compositional properties, which is an intentional counterpoint that we will return to.

Modularity elsewhere

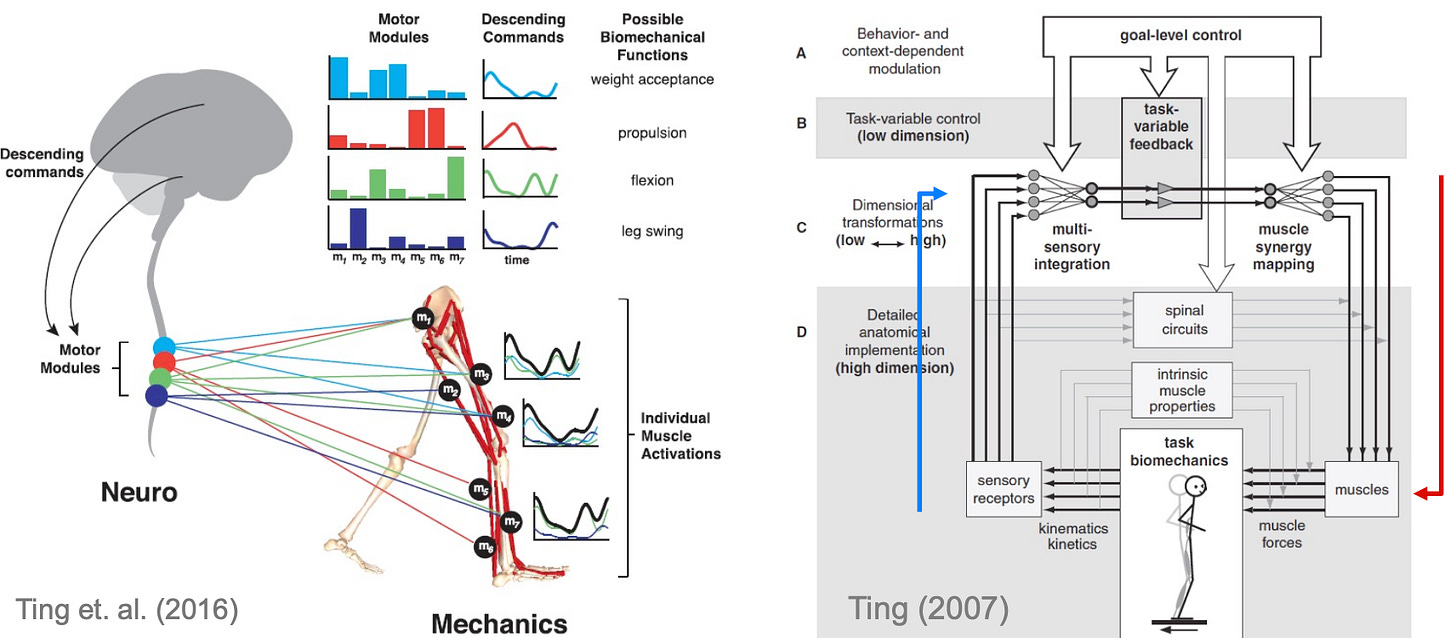

Deep learning did evolve from neural networks, which evoke biology right in the name. Biology has inspired many of the working principles of quadrupedal robots, including behavioral modularity.

Animals have an abundance of sensory inputs and muscle, but the number of task-level variables important to any particular task is a lot smaller (Ting (2007)). Going further, Ting et. al. (2015) argues that motor modules arise from neural plasticity in spinal structures that selective coordinate and co-activate multiple muscles. The result is that animals can control tasks like balancing in a hierarchical fashion, keeping the dimension of the task-space control low.

While robots typically have fewer actuators than an animal has muscles, each individual task will typically be overactuated for a general-purpose robot. For example, a humanoid robot will not need its arms to maintain a standing posture.

If we accept the presence of these motor modules, these patterns of activation could be re-used for different behaviors. Quoting Ting et. al. (2015):

Multifunctionality: muscles can contribute to many actions; a few muscles can be combined in many ways to produce a wide range of different actions.

Making equivalences to the synthetic disciplines, there is a clear connection to the idea of re-using behavioral modules, as we showed with Minitaur vertical hopper compositions.

Putting it all together, I’d argue that there are equivalences between biology and robotics in three distinct aspects of modularity:

Modularity benefits

Some of the benefits of modularity that are enjoyed by biological systems can also apply to the synthetic disciplines as well.

Motor modules can help navigate a “difficult-to-search and nonlinear set of neuromechanical solutions for movement” (Ting et. al. (2015)) as well as the “curse of dimensionality” in various engineering disciplines. This has clear implications on the computational requirements for algorithms.

A slightly less obvious use case for modularity is for optimizing robot design for flapping, jumping, etc., using coordinated movement patterns (or, template trajectories).

Real-world robotics

As robotics tools proliferate, their side-effects will start to also have a larger and larger impact on society.

Safety and predictability

The autonomous vehicle industry is possibly the first (but certainly not the last) subfield that has been thrust into the limelight of the question of safety of autonomous systems. The responsible peer-reviewed efforts of the first-party companies (e.g. Waymo) are huge steps in the right direction, but that is certainly not the end of the story.

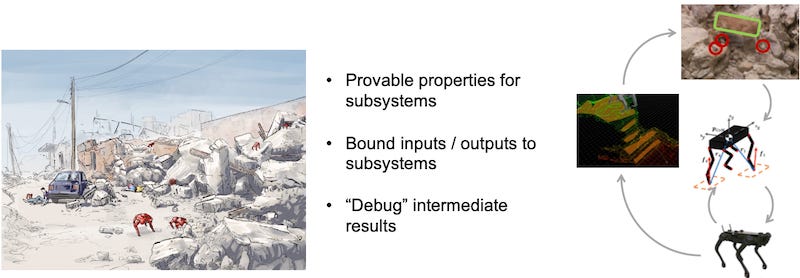

Robustness and multiple solutions inherent to a modular structure (as we saw above) is in stark contrast to the weakness of monolithic AI structures when subject to uncertainty (Cummings).

Intuitively, a modular architecture can be “debugged” and intermediate outputs can be logged and inspected. Just like a black box recording of an aircraft allows review of inputs made from the pilot to the machine, a modular structure allows insight into, and thresholding of, the function of individual modules:

Energy

While mechanical work done by robots necessarily needs energetic input (and the conversion efficiency can be quite high), the cost of computational work is nowhere close to the only known fundamental energetic limit based on Landauer’s principle.

Even as chips get more and more efficient, our appetite for computation outstrips those benefits, raising continual concern.

As already recognized by biology, a growing community of researchers are exploiting the fact that modular neural networks reduce power consumption.

The case for compositionality

Modularity comes with a price. The motor modules in humans have appeared over the (long) course of animal evolution, and the modular control structures developed for robots need to be hand-crafted. These processes are much less automatic, and need more work than scaling a simple structure with more data. In fact, the importance of pushing for architectural progress may not be limited to robotics (LeCun).

Additionally, modularity necessarily imposes limits on the space of usable methods or algorithms. For example, a modular controller reasoning with the equivalent of “motor modules” for a triple pendulum would never be able to accomplish this:

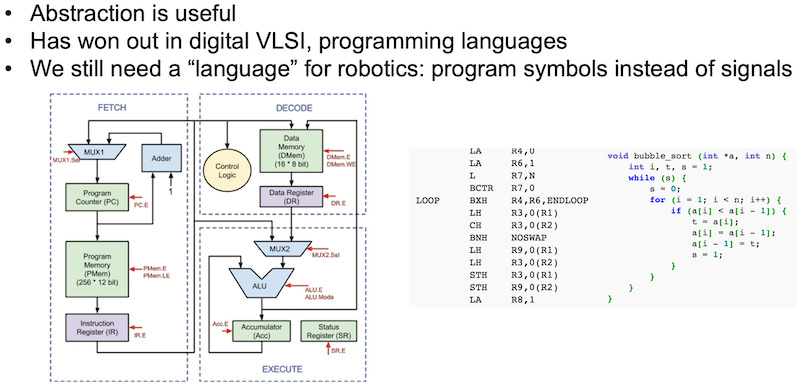

Nevertheless, the question of system abstraction with modularity has come up before in other fields such as digital VLSI and programming languages, and has clearly won out, in part due to the reasons discussed above.

We don’t yet have a generally accepted methodology or architecture in robotics that could be a foundation for symbolic behavior programming.

End-to-end deep neural networks have become a useful and generally-accepted architecture without compositional properties, but neural networks are not necessarily incompatible with compositionality (Hinton, Marcus). For more on this topic, I highly recommend the proceedings of this workshop on The Challenge of Compositionality for AI.

What is the path forward?

If we value the benefits of modularity discussed above, it will take more work to develop the correct architectures, but this work is essential to get to the point of robotics becoming a true scientific discipline with predictable outcomes.