"Is it learning?" Online motor adaptation in end-to-end robotics

Part 2: Where the low-level controller responds to the unexpected

This article is part of a series on end-to-end robotics pipelines:

This article

Coming soon

Last week, I wrote about modern end-to-end robotics pipelines; why this is the new north star, and the hidden architecture behind successful implementations. Part 1 reviewed some implementations showing signs of a cascade of a high-level (HL) → low-level (LL) controller in the actuation end of the pipeline:

I have first-hand experience demonstrating walking robots to customers in a sandy desert, and as the robots slipped they asked, “is it learning?” With the prior of people adapting their gait as they walk on ice (for example), a reasonable expectation is that an isolated robot can adjust its behavior after some trial & error or adaptation period.

However, this is not how naive foundation-model end-to-end pipelines (such as those covered in part 1) work today; a particular robot can only change its behavior once the “hive brain” is updated with new data in its training. Due to the size of these models, it is impractical that training happens on-device or frequently.

So, in part 2, we ask: how can a fielded robot adapt to unexpected conditions? Why do we even need adaptability? Given the HL → LL controller cascade structure in modern end-to-end pipelines from part 1, where does this adaptability live, and how does it affect the mapping to computing hardware? Lastly, we will also look at some published implementations and see how they approach or ignore this issue.

Updates to part 1, hot off the presses

Before we dig into part 2, I need to add a couple of updates from relevant news releases that I wasn’t able to review before part 1 was published (Jan 26):

Microsoft’s Rho-Alpha model announcement with commentary on Tech talks (Jan 24) reveals “split architecture” including dedicated low-level controller, underscoring at least two points in the part 1 post. (a) Tactile and proprioceptive information is incorporated in the action expert, showing that the action head facilitates feedback loops; (b) higher control bandwidth via so-called bypass mechanism. Quoting the post, “The long-term goal, Kolobov said, is to have the action expert or a part of it operate on proprioception and physical sensing modalities at a significantly higher frequency than on visual and language data.”

Figure Helix 02 Jan 27 update reveals new “System 0” controller, underscoring at least four points in the part 1 post. The “system 0” implementation is described as a dedicated whole-body controller (WBC), which conventionally converts desired accelerations or velocities to joint torques based on a model of the robot. (a) S1 went from controlling the upper body to the whole body, and this reduced the overall system complexity by separating concerns; (b) S0 and S1 incorporate tactile data in tighter feedback loops, without adding complexity to the large VLM S2; (c) S0 runs at a KHz rate increasing the last-level control bandwidth; (d) it is trained for that specific robot (vs. cross-embodiment), localizing robot body-related parameters in one place (and presumably enabling generalization of S2/S1 to a different robot). The purpose of the WBC is similar to the model-based reference in part 1, but the difference here is that it is also a neural network trained from data.1

I expect that we will continue to see further evidence and refinement of hierarchical control structures in commercial robots, vs. unstructured end-to-end pipelines. Make sure to subscribe to get future updates:

This publication and this post contain the author’s personal thoughts and opinions only, and do not reflect the views of any companies or institutions.

Why do we need adaptability?

When a robot leaves the lab and is in customers’ hands, it will at some point inevitably be subjected to an unexpected operating condition, stemming from component failure, perturbation, environmental condition, or operating condition (e.g. payload). To address this, one recourse is to build a large-enough model that has enough experience to handle all these situations (i.e. domain randomization, multi-embodiment, etc.). This of course takes (much) more data and more training, as OpenAI showed from their dexterity result in 2019:

The other option is adaptation in a strategic part of the pipeline to address as many of these variations as possible. In this post, we are focused on the action end of the pipeline, and the classes of variation we are interested in include variability in joints / motors (friction, motor torque), terrain properties, payload.

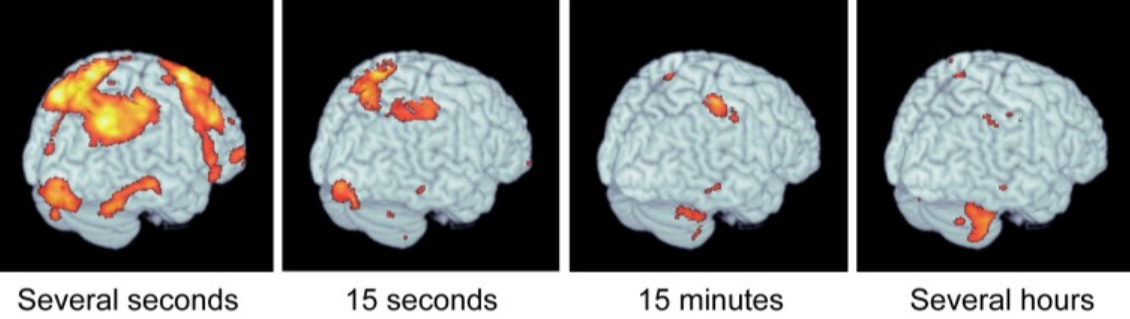

Let’s clarify the timescale hierarchy, because the word “adaptation” can refer to changes at various timescales. Within-movement corrections can happen in milliseconds, and is typically part of reactive control within the low-level controller. Skill acquisition across many tasks using large datasets during training will typically happen offline. The intermediate adjustment occurring in the seconds-to-minutes timescale, which we refer to as motor adaptation, is the focus of this post.

Historical context from biology, control theory, and LLMs

Cerebellar timescales (seconds to minutes) match closely with the motor adaptation timescale referred to above, and several research efforts identify its role in adaptation of behavior in that time range.

Morton (2006) further associates the cerebellum with motor adaptation and the spinal column to reactive control:

Cerebellar damage does not impair the ability to make reactive feedback-driven motor adaptations, but significantly disrupts predictive feedforward motor adaptations during splitbelt treadmill locomotion … The cerebellum seems to play an essential role in predictive but not reactive locomotor adjustments. We postulate that reactive adjustments may instead be predominantly controlled by lower neural centers, such as the spinal cord or brainstem.

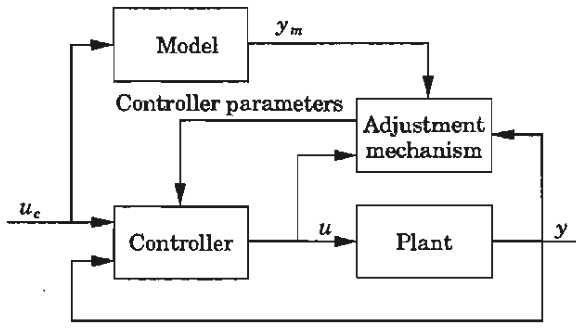

In control theory, there is a long tradition of adaptive control and model-reference adaptive control (MRAC) which utilize a (model-based) adjustment mechanism to modify the parameters of the controller.

The arrows in the figure above reveal a degree of interconnectedness beyond the cascade connections we primarily reviewed in part 1. The adjustment mechanism can also act in discrete steps instead of continuously, or without a model, in which cases it is called “gain scheduling”.

Self-improving learning systems are beginning to appear in the news more frequently in the LLM world: Ilya Sutskever said in Nov 2025, “There has been one big idea that everyone has been locked into, which is the self-improving AI”. The aforementioned Rho-Alpha model has an ability to update weights while running using teleoperation feedback. However, this can lead to a common side-effect called “catastrophic forgetting” due to all weights being in one huge monolithic structure, and so updates needed to be made either in judicious layers or in careful batches.

Motor adaptation in practice

One advantage in robotics pipelines is that they may (as we saw in part 1) have a hierarchical HL → LL structure. In such a situation, there are motor adaptations that can be integrated the LL controller without impacting the behavior of the HL controller, sidestepping the catastrophic forgetting issue.

I’ll go over a few illustrative examples, and especially discuss their ability to handle unexpected conditions. If I missed an idea that is pertinent and relevant, let me know in the comments:

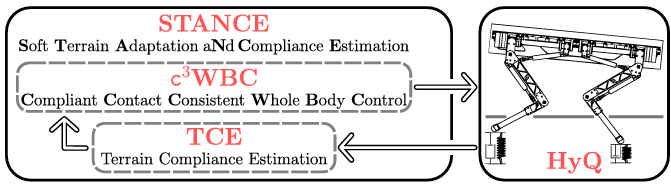

Adaptation in model-based LL control: robot arms, drones, humanoids

The pre-”end-to-end” era had many examples of adaptation in practice. Old ideas such as MRAC show up in industrial and commercial manipulators, such as in the payload estimation feature in Universal Robots arms. Commercial drones estimate wind to remain stable, sometimes using neural networks. In a 2019 HyQ paper, an explicit terrain compliance estimation module estimates parameters used by the LL controller. In a 2023 demonstration of the Atlas robot using model-based controllers while picking up heavy objects, Atlas “has access to the mass properties” of the object it is picking up, which I would lump into a gain-scheduling type of approach.

In all these examples, because the LL controller is model-based, it is easier to adapt for quantities like payload mass because it is clear where those terms appear in the controller. This is an advantage of having physically interpretable parameters, compared to black-box latent-space interconnections.

Mapping to computation:

HL → WBC inverse dynamics/QP (CPU) → Joint/servo controllers (microcontroller/CPU) → Torques

↑

*Adjustment mechanism (CPU/GPU)*Meta-learning for adapting among training environments

The concept of meta-learning (2019) is targeted at the motor adaptation problem, but needs samples over environments during training. This leads to the aforementioned prolonged training and large models, as well as susceptibility to truly unexpected (out-of-distribution) conditions. The authors of the paper are among the founders of Physical Intelligence, so it is possible that they could institute meta-learning-type methods for online adaptation in their action expert (not the case today as far as I can tell).

Mapping to computation of this hypothetical scenario:

VLM (GPU) → Action expert *with internal model and meta-learning* (GPU/CPU) → Trajectory tracking (CPU) → TorquesLearning-based latent parameter estimation for locomotion

As my sand locomotion example above might hint at, unexpected payload and terrain conditions are particularly prevalent in locomotion.

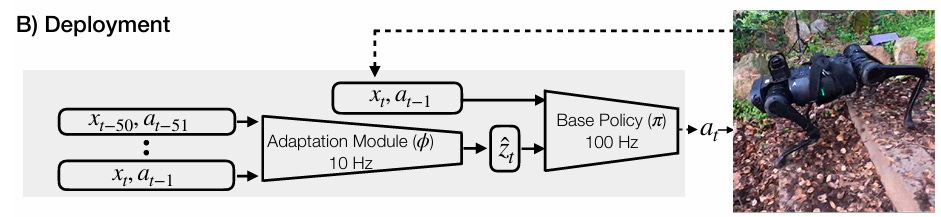

RMA: Rapid Motor Adaptation (2021) introduces a dedicated adaptation module that predicts a set of “latent parameters” that can adjust the action policy to better suit different conditions. These varied conditions are trained by randomizing in simulation, potentially suffering from a few of the same issues with out-of-distribution encounters and training difficulty.

One of the authors founded Skild.AI, and this quote from their Aug 2025 blog post

A striking aspect of our model is that it is not just robust, but it is also adaptive and graceful

(emphasis theirs) suggests incorporation of something like RMA. Absent too many details, here is my best guess of the composed pipeline mapped to computational hardware:

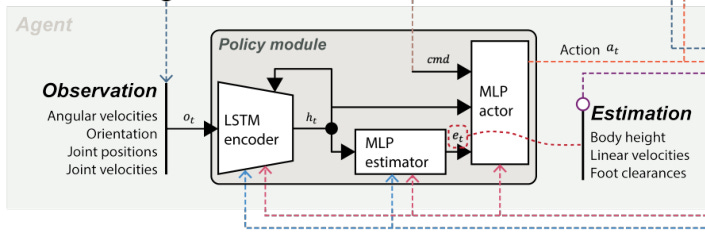

HL action policy (GPU) → *Adaptation module (GPU)* → LL action policy (GPU) → TorquesWhere RMA had a large-ish latent vector, there are similar approaches toward predicting parameters with more physical meaning, from a reduced or a full state estimate. These state-estimation networks concurrently learn base state and contact probabilities alongside policy, enabling better perception of ground interactions.

The end-result pipeline is quite similar, just potentially decomposing the adaptation module a bit:

HL command → *History encoder (GPU) → Estimator (GPU)* → Actor (GPU) → Impedance control (CPU) → TorquesIn-context learning to fix recent mistakes

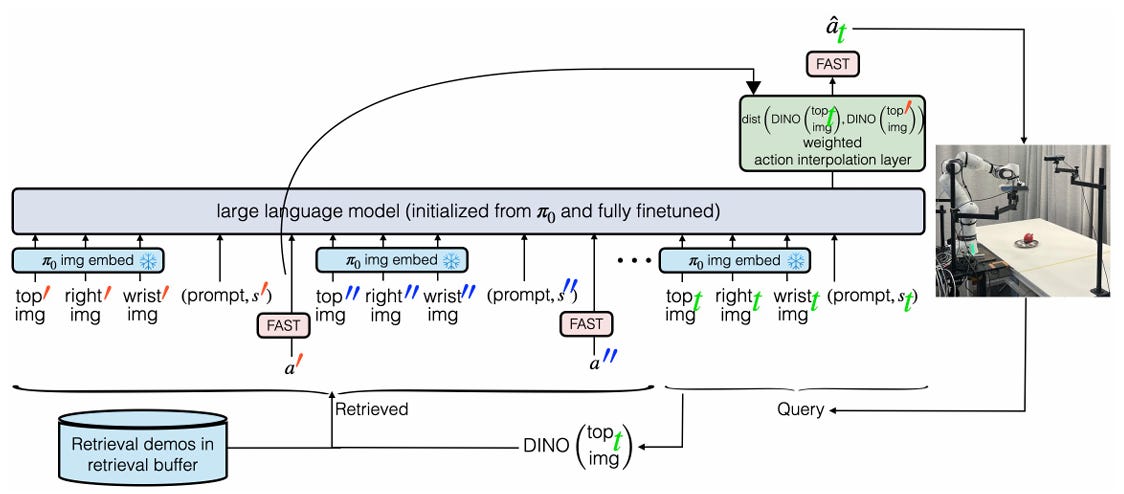

A different method called in-context learning (appearing in Covariant.AI’s Mar 2024 blog post, and in the RICL method from Aug 2025) attends to recent action history as opposed to encoded observation history. These relevant demonstrations are added to the VLA context before its forward pass.

The end-result pipeline adds retrieval buffer of demonstrations before the VLA, and an interpolation unit after the action module:

*Retrieval buffer* → VLM (GPU) → Action expert (GPU/CPU) → *Action interpolation (CPU/GPU)* → Trajectory tracking (CPU) → TorquesThis method is in a slightly different category, where relevant demonstrations need to occur and be reflected upon to adapt, compared to the potentially faster adaptation enabled by the previous methods. This strategy would not be sensible for time-sensitive or safety-critical tasks, but is categorically different and seemed worth reviewing.

Closing thoughts

In part 2 of this article series reviewing modern end-to-end robotics pipelines, we discussed why it may be useful to have some adaptation capability for fielded robots to handle unexpected conditions, and some examples of how it can be implemented. We also discussed some historical context from biology and control theory.

In part 3, we will try to get more hands-on and utilize what we learned from the first two parts to build up an effective pipeline from scratch. I’m still debating whether to use existing tools such as Isaac sim or build even more from first principles for clarity, so it may take some time before we get there. If you have any suggestions or feedback, let me know in the comments. If you found this article interesting, please share and subscribe for future posts. Thanks for reading!

It would be interesting to compare the complexity of a model-based vs. neural network implementation of this function (maybe we can try that in part 3).

I’m curious on your thoughts of having more layers instead of a pure 2 level HL->LL framework. It seems like humans do something like this with the cortex -> motor cortex -> brain stem/spinal cord. It’s interesting to see that Figure adopted this kind of hierarchy, any thoughts on the pros/cons on splitting the layered control architecture even more?

Also for what it’s worth I would vote for an IsaacSim implementation since it might be easier to have an RL pipeline that’s already kind of bundled together with active developer support than piecing together your own RL stack, sim, evals, etc. But idk it is always satisfying to piece together something from scratch haha

The progression from high-level to low-level control in end-to-end robotics is a crucial design pattern. Your breakdown of how motor adaptation fits into this hierarchy is insightful, especially the comparison to biological systems like the cerebellum's role in adaptation. The challenge of handling unexpected conditions without retraining the entire foundation model is exactly where adaptive low-level controllers shine. Looking forward to Part 3!