What Wiener knew about (artificial) intelligence in 1948

Cybernetics anticipated feedback, structure, and the human stakes of machine intelligence with unsettling precision

As evidenced by my prior post on von Neumann, I believe it’s crucial to integrate historical context and cross-disciplinary knowledge at this pivotal period of technological change. It was recommended to me that I read Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics, published even earlier and another pillar in the founding moment of the information age.

Wiener was a prodigious child, receiving a PhD by age 18 from Harvard, and becoming MIT mathematics faculty. By the account of Dark Hero of the Information Age, the biography by Flo Conway and Jim Siegelman, he was simultaneously one of the most intellectually alive and emotionally turbulent figures in twentieth-century science: touched by manic-depressive episodes and collegial feuds, yet capable of a mathematical breadth that few of his contemporaries could match.

That breadth is visible in the book he published in 1948: Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Its thesis was that information flow and message-passing are central to control and communication in both animals and machines. It appeared the same year as Shannon’s “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” and the year before Shockley’s transistor paper. Wiener was at the center of the founding of the information age, and yet he has been largely forgotten in the recent technological development. His legacy was overshadowed by Shannon, who had the more implementable theory, and by von Neumann, who had the more implementable architecture.

Reading Cybernetics now, almost 80 years later, is awe-inspiring and unsettling in equal measure. It is mathematically dense in places and dated in others, but the program it laid out is strikingly relevant to modern AI development. Here are the ideas from it that I found most resonant.

1. Feedback

“Cybernetics” originates from the Ancient Greek κυβερνήτης (kybernētēs), meaning “steersman” — the same root that, via Latin, gave us the word “governor.” It is perhaps not coincidence that Maxwell’s paper on governors was the first known exposition on feedback control. I don’t need to elaborate on the value of feedback in modern technology, but two nontrivial leaps Wiener makes are worth highlighting.

First, he draws a connection between communication and control in neurology. The feedback loop (sense the error, apply a correction, repeat) describes voluntary movement in biological systems. When this feedback is damaged, as in cerebellar injury, the result is a tremor or oscillation: too aggressive a correction followed by too aggressive a counter-correction. This convergence of engineering control theory and neurology was a founding observation of cybernetics: the same mathematics governs servomechanisms and nervous systems.

The second leap is the identification of a fundamental tradeoff: do you invest in modeling or in feedback? Wiener’s answer depends on how constant and knowable your system is. He called systems that leverage explicit models compensators, contrasting them with pure feedback mechanisms. In today’s terms, Wiener’s compensator needs a world model: an internal representation of how the system behaves that allows action without waiting for error to accumulate. The model vs. feedback tradeoff he identified has strong echoes of the one playing out now in the debate between scaling-based and structured AI architectures, not to mention in robotics. Model-free reinforcement learning is a direct descendant of the feedback side of this tradeoff: an agent interacts with an environment, receives a reward signal reflecting the gap between its behavior and a desired outcome, and adjusts its policy accordingly.

2. Neuron structure: digital vs. analog

Wiener asks in the book: in what ways are the computational substrates of brains and machines alike, and in what ways are they fundamentally different?

Wiener’s first observation is that neurons obey an “all-or-none” law (they fire fully or not at all) and in this sense are digital. This is in tension with von Neumann’s later analysis, covered in a prior post: von Neumann argued that individual neurons function more like small analog computers, with temporal dynamics and nonlinear integration beyond what a simple threshold element can do. The understanding of neuronal computation has deepened considerably since both accounts, and the honest answer is that neurons are neither purely one nor the other.

What followed from the digital view, at least in the engineering tradition, was eventually deep learning: stack enough simple threshold units to sufficient depth, and powerful computation emerges. But as the next sections argue, Wiener himself was skeptical that the generic stacking of simple units was sufficient.

3. Neuron organization: flexible vs. dedicated

What Wiener does not dispute is that even if neurons are digital in their firing, their organization is anything but generic. He writes:

The structure of our visual cortex is too highly organized, too specific, to lead us to suppose that it operates by what is after all a highly generalized mechanism.

As a mathematician, he frames this in terms of group theory: the visual system is built to be invariant under transformations of position, rotation, scale, and illumination. Image recognition is comparison at the level of structural properties that persist across transformations, and not comparison of photoreceptor signals. The retina has broadly distributed and low-resolution rod cells and foveally-concentrated cones, and layers beyond it extracting features at multiple spatial frequencies in parallel. Structure encoded by biology is doing work from the very first stage.

The unifying point is that the brain does not apply a general-purpose function to raw sensory data and let structure emerge. It applies a pipeline in which each stage is specifically organized to extract the right kind of information. Most modern vision models posit that this structure will emerge from scale and data; capsule networks, group-equivariant CNNs etc. attempt to encode it explicitly but remain outside the mainstream. This is the same tension at the heart of the world models debate: whether sufficient scale applied to a general architecture will recover the structure that biology built in deliberately, or whether that structure ought to be encoded.

4. The switchboard analogy

Wiener is next interested in how neurons are organized, and here his analysis diverges sharply from the digital computer model he was comparing against.

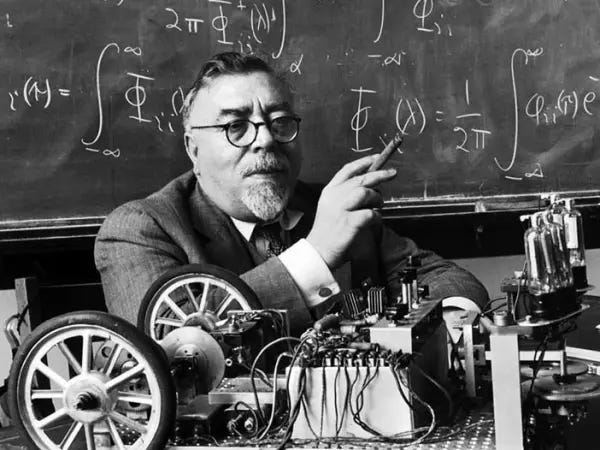

A digital computer of his era had specific circuits for specific operations: an adder, a multiplier, a comparator, each doing one thing reliably and repeatedly. The brain, he argues, does not work this way. Rather than dedicated permanent circuits, the brain reconfigures its functional connections dynamically, routing signals through different pathways depending on context. He uses the telephone switchboard as his analogy: the same physical wires serve different conversations depending on how the exchange is configured at any moment.

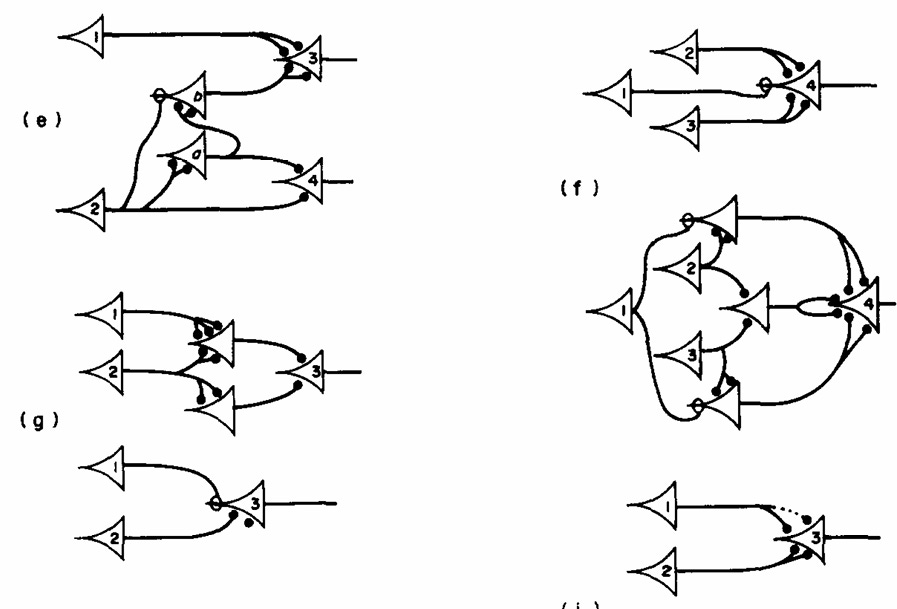

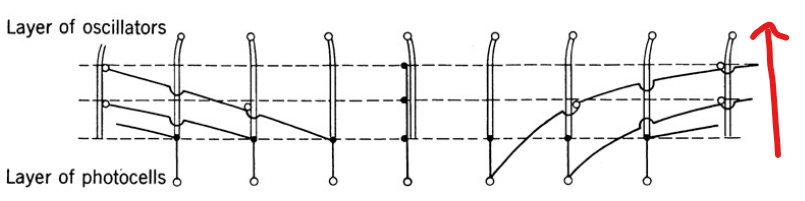

He makes this concrete with a visual processing example depicted above: recognizing a letter regardless of its size (a large “A” and a small “A”) with a fixed array of photocells. His proposed solution uses a switchable connection layer between the photocell array (bottom) and a fixed set of processing elements (top). By selecting different connection patterns (the diagonal lines), photocell activations at different scales get mapped onto the same processing elements, achieving scale invariance through reconfigurable routing rather than through a learned function. In deep learning perception, this is similar to ideas like spatial pyramid pooling or adaptive pooling.

In contrast, a vision transformer applies the same operation at every layer to every token, with flexibility coming entirely from learned weights at massive scale. There is no dynamic routing or reconfiguration based on the nature of the input. Wiener pointed out that this approach carries a cost: a large fixed architecture must run in its entirety even when most of it is irrelevant to the current input. A 175B parameter model processing a simple query still activates the full machinery, paying the energy and latency cost of elements that contribute nothing to that particular computation.

Some modern work moves toward Wiener’s direction. Mixture-of-experts architectures route inputs to specialized sub-networks rather than running everything; sparse transformers use dynamic attention patterns; early-exit networks use only as much compute as the input requires. These remain the exception rather than the rule, but they are each, in a real sense, implementations of the switchboard principle Wiener described in 1948.

5. Spatial efficiency: foveation

A thread running through Wiener’s treatment of vision is that the brain achieves capable perception not by processing everything uniformly and in parallel, but by being strategically non-uniform in both space and time.

The spatial side is foveation. The fovea provides high-resolution detail while the periphery offers broad, low-resolution motion detection. The brain doesn’t passively receive a full image, it actively steers the fovea toward informative regions via saccades, driven by a continuous feedback loop. The implication is that high-resolution processing is a scarce resource allocated dynamically, not applied uniformly.

6. Temporal efficiency: the television analogy

The temporal side is more surprising. Wiener observes that the brain may serialize what would otherwise require parallel hardware, using alpha waves (the ~10 Hz electrical rhythms visible in EEGs) as a scanning clock. Just as a television converts a two-dimensional image into a sequential stream by sweeping line by line, the brain may sweep through its representational space cyclically, interrogating stored patterns at each clock cycle. The efficiency principle is time-multiplexing: reuse the same hardware over time rather than duplicate it in space.

Together these describe a coherent alternative to the architecture modern AI has converged on. Transformers process all positions in a spatially uniform and temporally instantaneous manner, which is expensive in both compute and energy. Biology does neither: it allocates spatial resolution selectively and serializes computation over time. Foveation-inspired architectures (glimpse networks, recurrent attention models) and ideas like conditional computation point in this direction but remain outside the mainstream, largely because uniform dense operations map cleanly onto GPU hardware. Wiener’s architectural intuitions may become increasingly relevant if the AI energy crisis makes the efficiency argument more economically compelling.

7. Avoiding blunders: redundancy and verification

The brain produces behavior of remarkable precision despite individual neurons being surprisingly unreliable: they fire spontaneously, transmit probabilistically, and have far worse signal-to-noise ratios than transistors. Wiener’s answer, developed in the psychopathology chapter, is that there are two complementary strategies for error correction. The first is the “what I tell you three times is true” strategy: running two or three computing mechanisms simultaneously on the same problem, so that errors can be recognized by agreement across parallel channels. The second is backtracking: sequential verification where the system checks its own output and revises when something goes wrong. One is spatial (parallel redundancy), the other is temporal (serial correction) — the same tradeoff from before, now applied to reliability rather than perception.

This maps directly onto one of the most discussed failure modes in LLMs: hallucinations. Wiener suggests that they are the expected behavior of a system optimized for speed without redundancy or verification, not simply a quirk to be patched. A single forward pass through a transformer produces an answer with no mechanism for catching its own errors. Reasoning models which iterate, self-check, and backtrack are exploiting exactly the reliability/overhead tradeoff Wiener described:

But verification has limits. As I argued in the world models post, a system that lacks a grounded semantic model of the world can cross-check its outputs without ever catching the deeper class of errors that stem from not understanding what it’s talking about.

The human use of human beings

Wiener was clearly one of the founders of the information age, but he was also deeply worried about what was being built. A passage from his follow-up book The Human Use of Human Beings reads like something written last week:

The first industrial revolution was the devaluation of the human arm by the competition of machinery. The modern industrial revolution is similarly bound to devalue the human brain, at least in its simpler and more routine decisions. The average human being of mediocre attainments or less has nothing to sell that it is worth anyone’s money to buy.

He was not predicting this as an inevitable law of nature. His proposed answer was equally striking: rather than trying to preserve the market value of human labor artificially, he argued that society would need to restructure itself around non-market values like dignity, community, creativity, meaning. He wrote letters to labor unions warning them of what was coming, but he was not listened to.

In 2026, AI systems are starting to now inexpensively perform many of the cognitive tasks (writing, coding, analysis, translation, legal research) that defined middle-class professional employment in the twentieth century. The policy infrastructure to manage this transition does not exist. The urgency Wiener felt in 1950, when he had no working computer to point to, is more justified now.

Brian Christian, in his introduction to the recent reissue, calls Wiener “the progenitor of contemporary AI safety discourse.” That may be the most accurate short description of the man. He was not a pessimist or a technophobe — he was a technologist who had thought seriously about what he was building and felt obligated to say what it implied. That combination of technical depth, ethical seriousness, and willingness to deliver uncomfortable conclusions publicly is just one more reason to read and remember him.

I’m a strong proponent of reading and non-echo-chamber thinking. If you know of any other writing of this ilk, please let me know in the comments. If you liked this post, please share it, and subscribe!

This post draws primarily on “Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine” and the biography “Dark Hero of the Information Age”. It continues themes from previous posts on von Neumann and world models in AI.